Photo by Gage Skidmore via Wikimedia

Two men are making headlines, addressing the problems and the futures of their countries and the relationships between them.

One of them is Donald Trump, the newly-elected President of the United States. He is making it clear that he will push hard for renewed American strength at home, following up on his pledge to “Make America Great Again.”

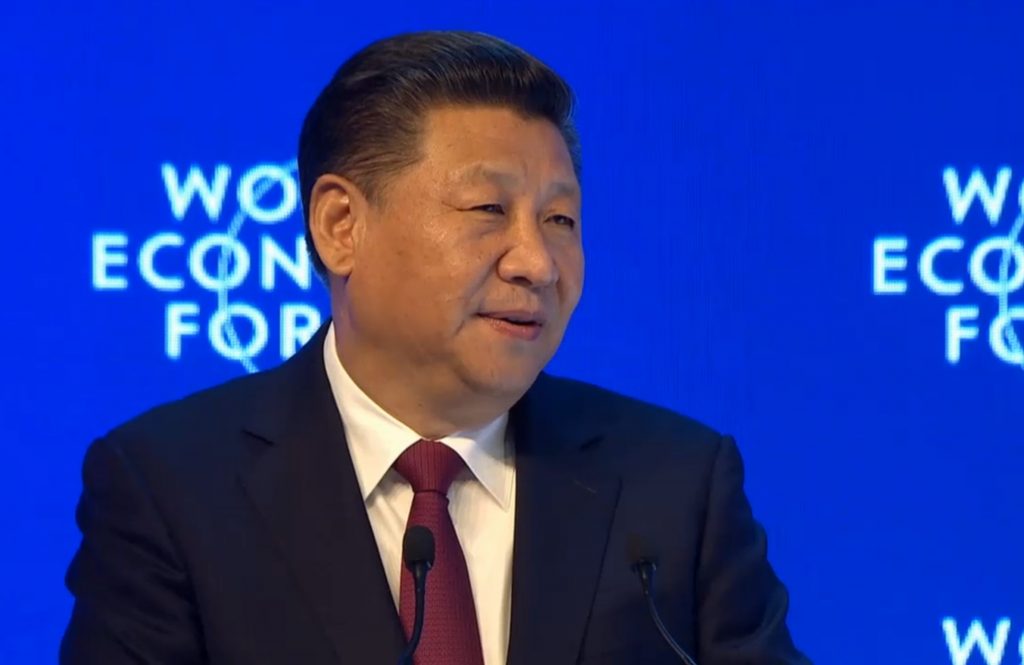

The second is Xi Jinping, the President of China. He is making it just as clear that he will push his own nation’s interests toward “inclusive globalization” in order to ensure “a human community with shared destiny.”

The political philosophies of both men are stimulated by the changing roles of their countries in world affairs; neither of the new roles has been clearly defined. Both Xi and Trump are seeking economic and political traction abroad; neither China nor the US are, at least for now, willing to trust the intentions of the other. Both are posing new challenges for established international norms. Neither appears willing to be influenced by internal critics or foreign governments.

There are numerous issues on the table as China and the US enter the next stage in the history of their relationship. Three issues – trade, the political and military role of each country in Asia, and mutual respect as reflected in bilateral diplomacy – will shape that relationship in the next few years. Here’s a look at what we know, for now.

Trade

China’s President Xi has put forward his vision for “inclusive globalization” at the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. In a speech to delegates – the first by a Chinese President at that international gathering – he reiterated criticisms expressed by Beijing following November’s US election of Donald Trump. Responding to Trump’s campaign threats to tax Chinese imports, Xi calling trade protectionist tariffs and other punitive trade policies “in the interest of no one.”

Trump said often as a candidate that China has been taking unfair advantage of American markets and industry by “using our country as a piggy bank,” luring US companies and manufacturers with cheap labor and low infrastructure costs. He promised that, if elected, he would put a stop to the off-shoring of American jobs by taxing Chinese imports with high tariffs. President Trump begins his term in office just as President Xi has warned that “trade protectionism will lead to isolation,” and that “no one will win in a trade war.”

On an international scale, leadership roles for both countries regarding trade issues have been taking shape, with tough talk and political charges on each side. Chinese officials have warned of consequences for the US if tariffs are imposed. Candidate Trump promised that if elected he would terminate the US role in the new Trans-Pacific Partnership, an 11-nation agreement forged in the last years of the Obama administration.

The original intent of the TPP was to break down trade barriers between countries in East Asia and Latin America, and to ensure a level playing field in dealings between those countries and China. The incoming Trump administration seems intent on pursuing a harder line in US-China trade relations, blaming past policies for American job losses. The newly-appointed US Trade Representative, Robert Lighthizer, has raised eyebrows by calling for retaliatory measures in the form of “very aggressive positions at the World Trade Organization.” Precise US policies regarding bilateral trade relations are yet to be developed; the US Congress, with both houses controlled by Republicans, is certain to be involved.

In the Pacific region, given the apparent demise of the TPP, the way has become more open for China’s own version of a regional trade pact. President Xi’s version of a free-trade philosophy has been emerging for some time, and not just as a counter-measure to Trump’s campaign speeches. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership – a 16-member organization that is still taking shape under Beijing’s auspices – is not likely to include US membership.

Roles in Asia

Since the Communist Party took control in 1949, a principal Chinese foreign policy has been to secure national sovereignty and compete for leadership roles in Asia. Early decades under Chairman Mao saw immense suffering among the country’s poor, harsh treatment of dissidents protesting government policies, and economic ruin in both cities and the countryside. Failed central government policies resulted in starvation and oppression and the deaths of tens of millions of Chinese.

The post-Mao era saw gains resulting from an opening of domestic markets, better education for Chinese citizens, a cautious embrace of limited democratic principles, and increased international acceptance. Diplomatic relations with the United States and membership in the World Trade Organization provided further stimulus to emerging domestic markets. Results included increased academic exchanges, rapid industrial development, and historic gains in reducing China’s ancient and widespread levels of poverty.

As China gained in wealth and stature, it moved to expand its sphere of influence in the Asia-Pacific region. By all indications, Beijing intends that that expansion will continue. This been evident most recently in the appearance of military bases and naval vessels in the South China Sea, a move that has caused concern for countries in East Asia’s coastal region, and for the United States. The US has enjoyed military dominance in the Pacific since the end of World War II, fighting two major wars and investing hundreds of billions of dollars in aid and recovery efforts to promote democracy in Asia. This US role has been a continual source of irritation in Beijing, and in the minds of most observers China believes that it is finally in a position to offer challenges – to America’s status as a world economic and political leader; and to what it regards as an intrusive American presence in the waters surrounding its national interests.

The new US president angered Beijing weeks ago by taking a phone call from the President of Taiwan, Tsai Ing-wen. The mere fact of the conversation – between the leader of Taiwan and the incoming President of the United States – set off an earthquake in the world of diplomacy. For thirty years after the end of the Communist Revolution in 1949, the US maintained diplomatic relations with the Nationalist government on Taiwan. That changed in 1979 when Washington shifted recognition from Taiwan to the mainland and the US and Beijing exchanged ambassadors. Since then, the relationship has rested on a one-China policy with Taiwan regarded as a part of China.

Reaction to the Trump phone conversation with the Taiwanese President was swift. Chinese officials warned the incoming administration of possible consequences if the time-honored policy was ignored, with state-controlled media calling Trump a “diplomatic rookie” and citing the phone call as a “provocation.” Trump responded in a Wall Street Journal interview, saying ‘everything is under negotiation, including ‘One China’.”

Beijing’s says the One China principle is the “political bedrock” of relations between the two countries. In mid-December the Chinese Ambassador to Washington said his government would never negotiate issues involving its national sovereignty or territorial integrity.

Mutual Respect

Prior to the start of the international meeting in Davos, the World Economic Forum published its annual Global Risks Report. One of its findings, based on the views of 750 international experts, is that “rising income and wealth disparity” is at the root of risks and tensions in various parts of the world. A second finding was a bit more ominous, warning of the inherent risks in the “increasing polarization of societies.” These trends, the report said, would likely have an impact over the next ten years or so.

The election of Donald Trump has been cited by bipartisan US political observers and others around the world as evidence of polarization in America – the widening gulf between demographic groups, increased racial and ethnic intolerance, the open hostility shown for dissenters and protesters at campaign rallies and political events.

This same polarization has been noted as affecting democracies elsewhere – in France and Britain and other parts of Europe, in the Philippines and Taiwan, in Bangladesh and India.

In this atmosphere of political tension within societies, it seems likely that tension would increase between governments and nations that might be more inclined, under less stressful conditions, simply agree to disagree and find ways to iron out differences. The same day that President Xi spoke of globalization in Davos, Agence France Presse reported the start of two days of military exercises in Taiwan. The Taiwanese government said it sought to reassure its people in the face of increased tensions with the mainland.

What’s Next?

As tension between China and the United States has increased in recent months – as China’s economic policies and military maneuvers in the western Pacific have prompted reaction from the American government – the state of the bilateral relationship has been shaken and, to a degree, changed.

In the eyes of President Xi, the clumsy overtures and “rookie” mistakes of the incoming US President are to blame. In the eyes of President Trump, the blame lies with the unfair and unjust policies of China in its dealings with America.

Do China and the United States respect each other? In the broadest sense they do, with each recognizing the benefits of normal bilateral relations. But that element of mutual respect – essential to any working relationship – is being tested, stressed by the forces of change more than at any time in decades. Diplomacy and respect based on mutual understanding will be of paramount importance in efforts to keep change under control on both sides.

It’s an odd time, too, given that China – for centuries, insulated by its policies and culture and language from the outside world – now openly seeks to embrace, as President Xi says, “a human community with a shared destiny.” Whereas the Chinese President seeks wider globalization, the new US President, Donald Trump, says globalization is at the heart of the problem in the United States, that he is determined to put “America First” – to “Make America Great Again” – in a manner reminiscent of the slogans of leaders in China not so many decades ago.

It is a pivotal time in the history of Chinese-American relations, and while the world looks on, no one is confident about what will happen next.

This piece is part of a series articles Views and News is publishing as a new US Administration assumes charge. Opinions expressed by writers do no necessarily reflect editorial views of the magazine.

An interesting and in depth article on US-China relations, no doubt that in last eight years US maintained relations with China and according to a press report the that only in 2016 people-to-people exchange between broke 5 million mark. Apparently as John Lennon also indicated [is hard to predict] that “what will happen next,” but there are signs and signals how the next Presidency will form its foreign policy. Let us hope for the best!