Photo: Hamed Malekpour via Wikimedia Commons

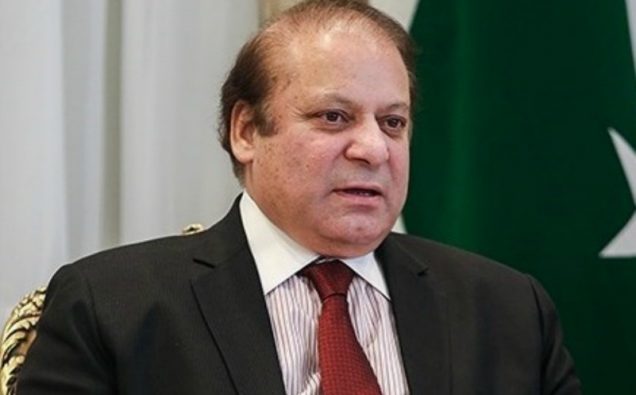

The damning Supreme Court verdict in the Panamagate case against the Sharif family marks unprecedented moral arraignment of a sitting prime minister from multiple angles – it denudes the highest elected office holder of the authority to rule the country; it documents Nawaz Sharif’s corruption-clouded dealings like a unique charge sheet from the highest levels of judiciary; and it gives him two months to leave the office constitutionally on his own or face a more embarrassing exit.

The surreal celebration by the Sharif brothers in a twitter-splashed photo was nothing but a whimper of a fallen ruling elite struggling for its voice. The formation of Joint Investigation Team to probe Sharif’s and his concealment of property form public purview and state records do not mean a sudden precipice after four decades of political dominance in the largest province and three times premiership of the country but a logical result of his dubious acts of dealing and wheeling.

No doubt, voters elected Sharif three times with a small ratio of counts being controversial. No doubt, Nawaz Sharif filled in the vacuum in Punjab that PPP’s sagging image created. No doubt, Sharif built some visible infrastructure projects and outperformed the last PPP government, although some of the projects are misplaced priorities.

But Nawaz Sharif also boxed himself into a tight corner -surrounding himself with cronies and lackeys, and putting loyalty ahead of merit, integrity and the country, each time he made it to the corridors of power. Critics point out that Sharif repeated the practice each time he was elected, ostensibly to hide his acts of omissions and commissions and, as doubted in this case, possibly to launder billions out of the country. As the judgement and incisive remarks by the judges – from the Godfather analogy to rejection of the Qatari Prince’s letter as bogus – suggest, the Mayfair apartments may just be tip of the iceberg.

That Sharif has no recourse but to leave is too obvious to ignore. The least he can do is to leave the office and let an in-house change take place constitutionally so that country is spared another dreadful bout of instability, and the JIT is able to look into charges against him independently.

At a time, when Pakistan is poised to grow economically – in small part to the Sharif government’s management – such exit may provide the billionaire prime minister some reprieve. Though a thought of it might sound a little jittery in the face of PPP joining the political PTI-led clamor against the Sharif. Despite the judges’ vote of no confidence, Sharif has not changed the head of National Accountability Bureau.

But Pakistan also needs something more – the noise around the Panamagate should not drown out the demand for across-the-board accountability of all national actors. Not just the Sharifs but all those civilian and former military officials, who served in powerful positions of governance and face corruption charges, must bow before the law. But such a process must begin now with the Panamagate opportunity.