What makes the process a never-ending election season

During his campaign for the White House Donald Trump said many times that he intended to turn the United States around. His predecessors and Washington politicians had allowed the country to crumble, he said, and millions of Americans couldn’t earn a decent living. As President, he would reverse the decline of the nation’s economy and lift up the downtrodden middle class. Coal miners would be back at work, jobs would be brought back from overseas, factories would be humming again, tax reform would bring financial relief to hard-working citizens, and Americans without a job would be able to find one.

As President, Trump promised, he would repeal and replace Obamacare, fix the country’s roads and bridges, tear up unfair trade agreements, and walk away from the nuclear weapons pact with Iran – one of the worst, he said, in the history of the country. Obama-era regulations would be scrapped – along with the crippling effects of the multi-national Paris accord on climate change. He told the Republican National Convention that the country was broken, that only he could fix it – that only he could “make America great again” – and that to do it, he would drain the swamp in Washington and disrupt the comforts and unproductive behaviors of its long-time denizens.

At a New York rally before the election he said, “you’re going to be so proud of your country…we’re going to start winning again. We’re going to win so much,” he said, “you may even get tired of winning.” People at the rally cheered loudly – as did supporters at more rallies in other towns and cities – and politicians everywhere began to see that Trump had struck a chord with the voters.

Months later, despite intense opposition in Republican primaries, despite scandals and controversies and bad press and numerous detractors, despite his lack of political experience – and a Democratic opponent who had been First Lady, a United States Senator, and Secretary of State – despite all that, Donald Trump made good on his pledge to win the 2016 presidential election. He had said from the beginning that he would win, and while most political observers – including some of his closest campaign advisers – thought he would not, he did; one of four candidates in America’s 240-year history to win the presidency in the Electoral College while losing the popular vote.

The inaugural parade last January 20th left waves of mixed feelings in its wake, as many in the U.S. and around the world wondered what the Trump presidency would be like.

Promises are sometimes hard to keep

Since coming into office a year ago, President Trump has had some difficulty keeping many of the big promises made during his campaign. Despite Republican control of both the Senate and House of Representatives there has been no repeal of Obamacare, and no broad legislative effort to repair the nation’s infrastructure; comprehensive reform of U.S. tax laws remains elusive.

Trump has declared that America will withdraw from the Paris accord on climate change, the nuclear weapons agreement with Iran, and the trans-Pacific trade agreement – three major components of Barack Obama’s legacy in foreign affairs – but all remain in force pending further action. His administration has pulled back numerous Obama-era initiatives aimed at regulating businesses and banks, controlling pollution, enforcing civil rights laws, and protecting the environment. He has told allies in Europe and Asia that they must pay more for U.S. support; he has both criticized and praised China for its trade practices; he has continued to pledge construction of a wall on America’s border with Mexico; and, he has engaged in a long-distance shouting match with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un – raising apprehensions about the possibility of nuclear war. The President’s one clear victory came with the appointment and confirmation of Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch, an accomplished jurist and a favorite of legal conservatives.

Against this backdrop, and all the distractions and controversies that Trump’s provocative use of social media have aroused, the political life of the nation has, by the accounts of academics, historians, and media experts – and as reflected in numerous opinion polls – become more divisive than most people can remember. Disruption of cultural norms, some of which were already quite fragile, has widened the gaps in trust between racial and ethnic demographics, religious groups, economic classes, and genders – with many who were doubtful about Trump during the campaign now feeling they have reasons to oppose him.

At the beginning of the President’s first year in office, the Gallup poll showed that nearly two-thirds of Americans believed that Trump would keep his promises, and that – despite his lack of political experience – he would be a strong and decisive leader. Even though he failed to win the popular vote in the election, more than half of Americans said after the inauguration that he would bring about changes that the nation needed. In the early months of 2017 those numbers fell rapidly, and after one year in office Trump’s approval rating – as measured by five different polling organizations – fell below 40%. Two-thirds of those polled in early November said Trump had accomplished “not much”, or “little or nothing.” And, because of its failure to pass any of the legislative measures promised by Trump and the Republican-controlled legislature, Congress’s numbers are even lower. In early November of this year the job approval rating for the U.S. Congress, as measured by the Economist, was nine percent – that’s right, 9%.

In addition to the lack of major legislative achievements, there are other reasons why Americans are taking a harder look at the Trump administration, in spite of the fact that the White House can hardly be blamed for all the nation’s problems. The rise of the so-called alt-right political movement, with its blatant white nationalist sentiments against Jews, immigrants, and people of color, has prompted many to express concern that the Federal government’s response hasn’t been strong enough. Mass shootings in several states have heightened opposition to lax controls on the sale of firearms. Attacks against Muslims and mosques are seen as having been encouraged by President Trump’s effort to tighten controls on immigration from certain Muslim countries. Women are speaking out in greater numbers about unfair labor practices, cuts in government programs that benefit children and families, and against longtime cultural codes of sexual conduct that seemingly condoned unwanted advances – even attacks – by men.

These and other divisive issues, fairly or not, are seen through the prism of Trump’s impact on national life. Increasingly, people are prone to see a connection between his antagonistic approach to individuals and groups and the growing coarseness of social and cultural relationships. There’s a sense, as measured by political scientists and poll takers, that the American people are less willing to listen to each other and more willing to argue, and blame, and harbor resentments. And no matter what side people are on, everyone seems to feel that these are not America’s best days.

Politics, but bot as usual

In this increasingly edgy and noisy social and cultural environment, the nation’s political life has stumbled forward. The lack of legislative achievements in the Republican-controlled Congress, coupled with the confrontational and often abrasive style of President Trump, have turned up the heat on the members and leaders in both the House and Senate. Hopes in Congress and in the electorate for sweeping changes in the way Washington works have slowly dissipated – swept aside by conflicts over both substance and style – and have given way to discussions as to whether or not the Republican Party is capable of governing.

This perception of the GOP as a feckless and unproductive collection of warring factions – led by a President whose seemingly uncontrollable use of Twitter serves as his primary communications link to the public – contributed heavily to losses in early November by Republicans across the United States. Democratic candidates for Governor were swept into office in New Jersey and Virginia and Washington State. Other state and local races across the country saw Democrats win seats, with a large percentage decided in favor of women – some of whom had never before run for political office.

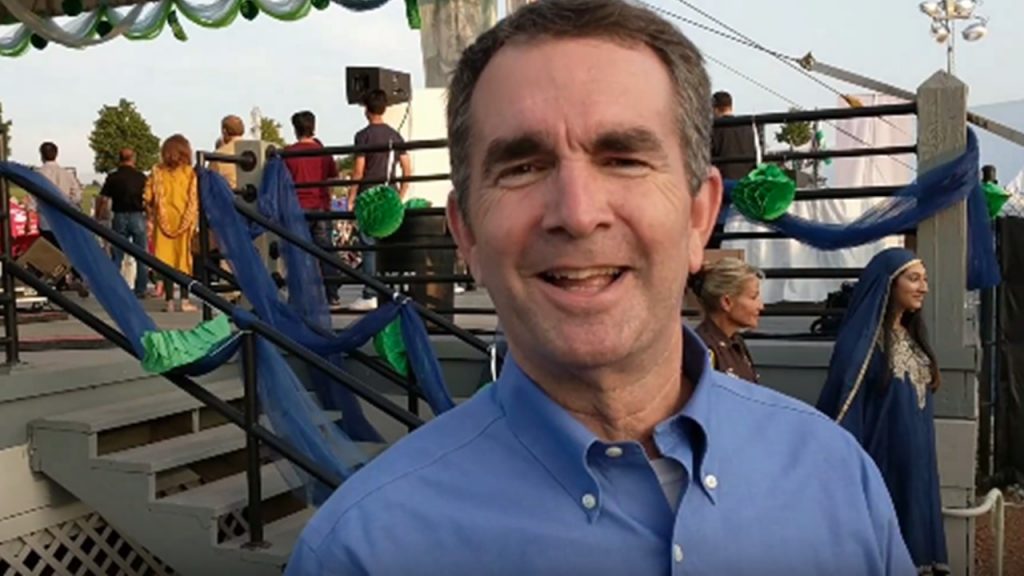

Ralph Northam speaking to Views News TV as candidate at a Pakistan Independence Day event in Virginia August 2017

If Election Day a year ago was a resounding victory for Republicans, this year it was a day of widespread victories for Democrats – much of it because of voter dissatisfaction with a Congress and White House that had failed to keep promises and had, instead, raised popular anxieties and the nation’s blood pressure.

But elections, as many historians have noted, are often akin to snapshots, reflections of a moment in time, rather than the beginning or the end of a long-term trend. That certainly seems true as 2017 comes to a close.

The Republican Party is battered by its low marks for performance, and by the fractures and divisiveness within its ranks. Whether or not it can come together in time to stage effective campaigns for Party candidates one year from now – the “off-year” election of 2018 – will determine the fate of its leadership in Congress, and perhaps of the presidency in the election of 2020. But the Democratic Party, despite this year’s wins, is in no better shape. Equally battered and bruised by internal splits between wings of the Party and by its devastating loss of the White House in 2016, the Party faces the daunting task of healing those bruises and uniting divided factions in time for the off-year campaigns next Fall, and the presidential election in 2020.

It’s an accident of history, perhaps, that the two political parties – unable to agree at almost any level on policy issues, governing philosophy, or simple approaches to solving problems – suffer from the same crippling ailment: neither is able to project a clear and unified message to voters as to what it stands for. Thus, a pattern is settling in, that voters are growing used to casting ballots against – rather than for – a Party or a candidate. Elections, increasingly, seem to be fueled by negative energy.

Stark choices for the political parties

By this reasoning, those who study American politics generally agree that voters rejected the status quo in 2016, thus bringing in Donald Trump. One year later, voters in local races across the country rejected Republican candidates – and the politics of Donald Trump – in favor of change. In this never-ending campaign season the American electorate, stimulated by growing distaste for political posturing and a lack of responsible governance, will take a measure of office holders who are running again in 2018.

The pressure is on for both Republicans and Democrats to provide leadership for America’s government, services for the American people, and strong alliances for America’s partners around the world. If those things don’t happen, we can look for changes again a year from now – and, perhaps, in the presidential election in 2020.