Minar-e-Pakistan in Lahore, where Pakistan Resolution was passed Photo: Lime.adeel/Wikimedia Commons

The debate around the definition of Islam and its relationship to Pakistan’s identity has become vitriolic, obfuscating and violent. It also threatens a breakdown of law and order across Pakistan. The recent protests in Islamabad ended in deaths, angry protests, and the closure of schools, all in the name of demanding the heads of central ministers over accusations of blasphemy. In the meantime, Peshawar once again saw an educational center attacked and students brutally killed.

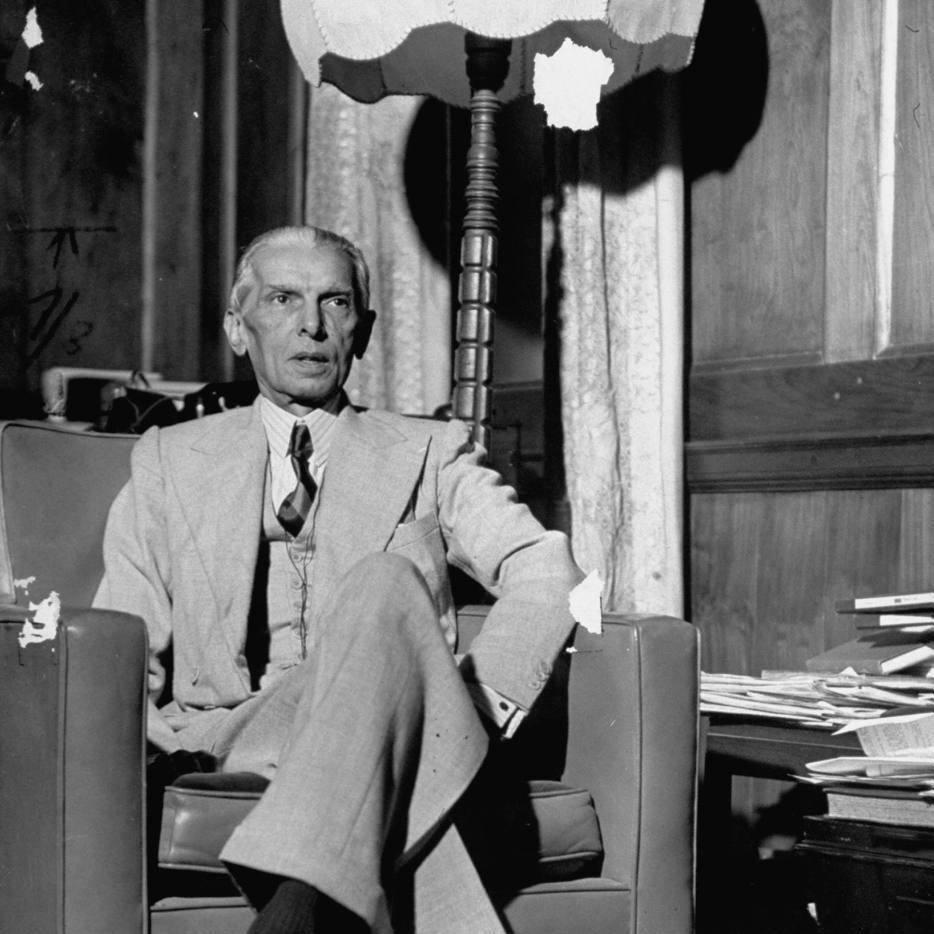

It is a matter of some urgency then for Pakistanis to step back and examine what exactly was the Quaid’s vision for the new nation he created; what better time than when Pakistan celebrates his birthday on 25 December.

Instead of imposing our personal opinions on Jinnah’s ideas, the most accurate way to understand him is to read what he said, study his actions and listen to those who knew him. Forcing him into a “secular” category or an “orthodox” one is a futile exercise. People cannot just make up things; that is called “fake news.”

Understanding the central importance of Jinnah to Pakistan, I spent a full decade of my life creating and completing the Jinnah Quartet, which featured Jinnah (1998), starring Sir Christopher Lee, the documentary Mr Jinnah: The Making of Pakistan (1997), the academic study Jinnah, Pakistan, and Islamic Identity: The Search for Saladin (1997); and a graphic novel, The Quaid: Jinnah and the Story of Pakistan (1997) (for further information please see the documentary, Dare to Dream- The Making of Jinnah (1998) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VKmJFbWXuzc&authuser=0). This ambitious project was only completed due to the dedication of numerous people each one contributing in different capacities.

To my mind, perhaps no words better frame Jinnah’s vision for Pakistan than two hallmark speeches he gave in August 1947, as I pointed out in my book on Jinnah and from which the following excerpts and quotes are taken. The first was delivered on 11 August, when the Constituent Assembly elected him as its first President, the second speech on 14 August. Together they comprise the essence of Jinnah’s thought, his defining statement, his “Gettysburg Address.”Perhaps his most significant and most moving speech was the first one. It is an outpouring of ideas on the state and the nature of society, almost a stream of consciousness. No bureaucratic hand impedes the flow because it was delivered without notes:

“Now, if we want to make this great State of Pakistan happy and prosperous we should wholly and solely concentrate on the well-being of the people, and especially of the masses and the poor. If you will work in co-operation, forgetting the past, burying the hatchet, you are bound to succeed. If you change your past and work together in a spirit that every one of you, no matter to what community he belongs, no matter what relations he had with you in the past, no matter what is his colour, caste or creed, is first, second and last a citizen of this State with equal rights, privileges and obligations, there will be no end to the progress you will make.

I cannot emphasize it too much. We should begin to work in that spirit and in course of time all these angularities of the majority and minority communities, the Hindu community and the Muslim community – because even as regards Muslims you have Pathans, Punjabis, Shias, Sunnis and so on and among Hindus you have Brahmins, Vashnavas, Khatris, also Bengalees, Madrasis and so on – will vanish. Indeed if you ask me this has been the biggest hindrance in the way of India to attain the freedom and independence and but for this we would have been free peoples long long ago.”

Building up from this powerful passage comes the vision of a brave new world, consciously an improvement in its spirit of tolerance on the old world he has just rejected:

“You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place of worship in this State of Pakistan…. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed – that has nothing to do with the business of the State…. We are starting in the days when there is no discrimination, no distinction between one community and another, no discrimination between one caste or creed and another. We are starting with this fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of one State.”

Jinnah also pledged: “My guiding principle will be justice and complete impartiality, and I am sure that with your support and co-operation, I can look forward to Pakistan becoming one of the greatest nations of the world.”

Two days later the Mountbattens flew to Karachi to help celebrate the formal transfer of power. In his formal speech to the Constituent Assembly on 14 August, Lord Mountbatten offered the example of Akbar the Great as the model of a tolerant Muslim ruler for Pakistan.

Mountbatten had suggested Akbar advisedly. Akbar had always been a favorite of those who believed in inclusive cultural synthesis or what in our time passes for secular. To most non-Muslims in South Asia, Akbar symbolized a tolerant, humane Muslim, one they could do business with. He avoided eating beef because the cow was sacred to the Hindus. The proud Rajputs gave his armies leading generals and his court influential wives.

But for many Muslims Akbar posed certain problems. Although he was a great king by many standards, he was a far from ideal Muslim ruler: there was too much of the willful Oriental despot in his behavior. His harem was said to number a thousand wives. His drinking, his drugs and his blood lust were excessive even by Mughal standards. In a fit of rage he had some 30,000 people massacred in a campaign because they dared to resist him. Akbar also introduced a new religious philosophy, din-e-ilahi, a hotchpotch of some of the established religions, with Akbar himself as a focal religious point. This was imperial capriciousness, little else; and it made the ulema unhappy.

Mountbatten would have been aware that six Mughal emperors, beginning with Babar in 1526 and ending with Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, had ruled India, giving it one of the most glorious periods of its history. So his choice was neither random nor illogical. Yet he could also have selected Babar, who after all opened a new chapter of history in India, not unlike Jinnah. The story of Babar – poet, autobiographer, loyal friend and devoted father – was perhaps too triumphalist for Mountbatten.

But had Mountbatten and his staff done their homework they would have realized their blunder. In suggesting Akbar, Mountbatten was clearly unaware of the impression he was conveying. While his choice may have impressed some modernized Muslims, the majority would have thought it odd. Of the six great Mughal emperors from Babar to Aurangzeb, Akbar is perhaps the one most self-avowedly neutral to Islam. To propose Akbar as an ideal ruler to a newly formed and self-consciously post-colonial Muslim nation was rather like suggesting to a convention of Muslim writers meeting in Iran or Saudi Arabia in the 1990s after the publication of The Satanic Verses that their literary model should be Salman Rushdie.

Akbar was the litmus test for Jinnah. Perhaps earlier in his life he may have considered Akbar, but now he rejected the suggestion. In a rebuttal which amounted to a public snub — Mountbatten was after all still the Viceroy of India — Jinnah presented an alternative model, that of the holy Prophet of Islam (pbuh):

The tolerance and goodwill that great Emperor Akbar showed to all the non-Muslims is not of recent origin. It dates back thirteen centuries ago when our Prophet not only by words but by deeds treated the Jews and Christians, after he had conquered them, with the utmost tolerance and regard and respect for their faith and beliefs. The whole history of Muslims, wherever they ruled, is replete with those humane and great principles which should be followed and practiced.

Jinnah reverted to the themes he had raised only three days earlier. The holy Prophet had not only created a new state but had laid down the principles on which it could be organized and conducted. These principles were rooted in a compassionate understanding of society and the notions of justice and tolerance. Jinnah emphasized the special treatment the Prophet accorded to the minorities. Morality, piety, human tolerance – a society where color and race did not matter: the Prophet had laid down a charter for political and social behavior thirteen centuries before the United Nations.

The Dharmshala & Hindu Temple at Saidur Village Photo: MohammadOmer/Wikimedia Commons

Jinnah’s remarks must be seen in the context of Islamic culture and history. Jinnah, conscious that this was one of the last times he would be addressing his people because he was dying, would find himself echoing the holy Prophet’s own last message on Mount Arafat. For him too this was the summing up of his life and his achievement.

While rejecting the idea of a “theocratic” state, the Quaid’s speeches emphasized the need for Pakistan to draw inspiration from the “high principles” of the Quran and the holy Prophet. Reading Jinnah’s speeches, it is clear that in his vision Pakistan would be an ideal Islamic society that would be equitable, compassionate and tolerant and from which the “poison” of corruption, nepotism, mismanagement and inefficiency would be eradicated. This was also a society in which minorities would be treated with dignity and respect, not excluded from public life simply because of their faith or ethnicity.

We have heard the Quaid’s own words above. Let us look at his actions to find clues as to how he interpreted his faith.

Here is a glimpse of Jinnah’s attitude to Islam when he was a young man. It has been said that Jinnah chose Lincoln’s Inn because he saw the name of the holy Prophet at the entrance. I went to Lincoln’s Inn looking for the name on the gate, but there is no such gate nor any names. There is, however, a gigantic mural covering one entire wall in the main dining hall of Lincoln’s Inn. Painted on it are some of the most influential lawgivers of history, like Moses, and, indeed, the holy Prophet of Islam. A key at the bottom of the painting confirms the names. Jinnah, I suspect, was not deliberately concealing the memory of his youth but recalling an association half a century after it had taken place. He had remembered there was a link, a genuine appreciation of Islam. Had those who have written about Jinnah’s recollection bothered to visit Lincoln’s Inn the mystery would have been solved.

After the creation of Pakistan, it was precisely this broad and inclusive idea of Islam that led the Quaid to spend his last Christmas before he died in a church with the Christian community, declare himself Protector General of the Hindu minority, and appoint a Hindu and Ahmadi to key posts in his small cabinet.

Dina, his daughter and only child, sums up her father’s position on his faith in a rare interview she gave us for the Jinnah documentary: “He was not a religious man, but he wasn’t irreligious either. There was no big religious thing.”

Jinnah’s dream for Pakistan was a grand one: what he wanted was nothing less than that Pakistan become “one of the greatest nations of the world,” not just in the Muslim world. Yet today, the idea of Pakistan is greater than the reality. At this very critical time, Pakistan is facing major external and internal challenges. Without a clear moral and political compass, Pakistanis will remain confused, divided and prone to anger and even violence as to how best face the growing challenges such as those posed by the protesters who recently blockaded Islamabad. Pakistanis must look back at Jinnah’s Gettysburg Address and re-imagine their own future as a people and as a nation.

![By Swerveut at English Wikipedia (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.viewsnews.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Karachi_St._Patricks_Cathedral-1024x732.jpg)