For much of the past decade, negative mentioning of Pakistan and Pakistanis has been a norm in Washington. It was, therefore, a refreshing break to witness a select gathering of a cross-section of Washington luminaries to acknowledge the passing, to celebrate the life, and to honor the memory of Dr Ayub Ommaya, one of the world’s leading neurosurgeons and neuroscientists, as well as an authority on brain injury who had enriched the medical profession of the United States and touched the lives of thousands.

Ayub was born in Mian Channu, Punjab, in 1930, and died in Islamabad this year. But much of his professional life and scientific achievements were concentrated in the Washington area.

Along with Dr Barry Blumberg, winner of 1976 Nobel Prize in Medicine, and retired US Senator Paul Sarbanes, co-author of the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act that led to major reform of the accounting profession – both Rhodes Scholar batch-mates of Ayub during the 1950’s at Oxford – this scribe, among others, was asked to deliver remarks at the memorial meeting held in the Washington area on a cold November afternoon.

One landmark feat of Ayub was to develop an effective way to deliver chemotherapy treatment to those suffering with brain tumours. He invented the tool called the Ommaya Reservoir, which is today in worldwide usage. His contributions were not limited to his profession. During the massacre of Muslims over 15 years ago, Ayub personally funded the trip of a Bosnian leader to Washington so that he could present his case before US policy makers. A recurring theme of the speakers was Ayub’s humanity, humility, and helpful nature.

Identified among his special traits was a twinkling smile, his being a dreamer, and a child-like curiosity which endowed Ayub with a moral imagination to pursue scientific inquiry. An avid reader with his own personal library, one of Ayub’s pet projects was to constantly seek the link between Islam and science.

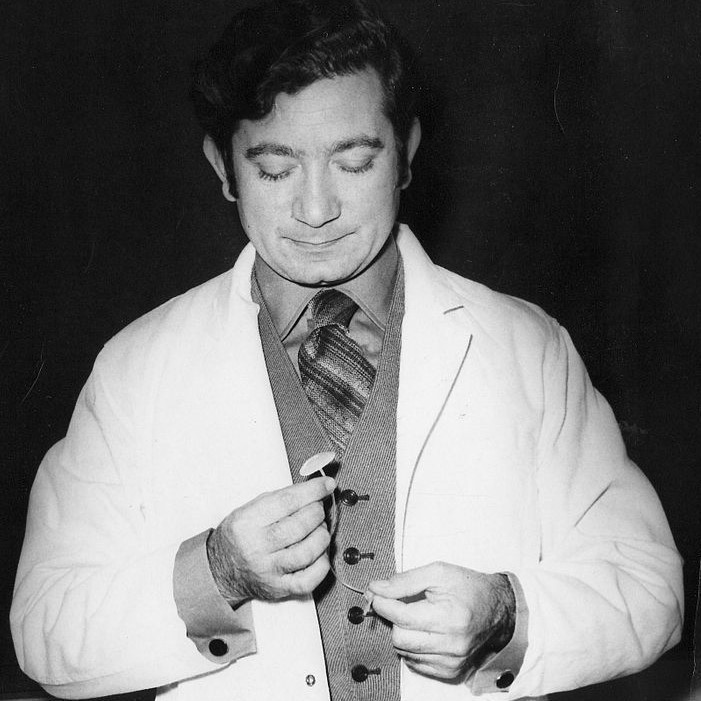

Photo: Mowahid Shah collection

Dr Ron Uscinski, his long-time friend and fellow neurosurgeon, mentioned Ayub’s love for cinema and song. According to Uscinski, Ayub was “a towering, multifaceted intellect, who could converse easily on such subjects as Italian opera, old movies, Sufism, the origins of Urdu …He always seemed to be able to see beyond the immediate situation, and had an uncanny ability to pull diverse and seemingly unrelated observations together into a clear picture that made one ask oneself; ‘now, why didn’t I see that!'”

A weakness in American culture is its being overly scheduled and overly programmed. Ayub, with his zest for living, recognised that the key to breaking the chains of crippling routine was spontaneity. He could, on the spur of the moment, get up to go to a movie, join in an outing, or invite a friend for an impromptu dinner which he would cook himself and then regale the occasion by singing an Italian opera song.

The memorial meeting showed that what sustains human connections is not necessarily similarity of culture, language, temperament, or ethnicity, but a similarity of spirit. It also re-affirmed that a legacy of remembrance is not secured by depositing billions abroad but by giving hope to the hopeless and giving comfort to those in pain.

Ayub Khan Ommaya, MD, ScD (h.c.), FRCS, FACS (April 14, 1930, Mian Channu – July 11, 2008, Islamabad)/Wikipedia

Ayub was full of life and parts of his life were not easy. Yet, he retained his humour and laughter in difficult circumstances.

The joy of living is in giving joy to others.

One of the dilemmas of contemporary Muslim society is its incapacity to come up with inspirational role models for the youth to emulate. In this vacuum, many seek celebrities and look up to entertainers, rock stars, or those wielding power and flaunting big money. Adding to the problem is the in-built culture of compliance caused by a colonial legacy and dependency on external forces. Defeatist conformism and frustrations with a seemingly dead-end status quo contribute to a sense of powerlessness that gives space for nihilistic frenzy to flourish. One way to blunt destructive impulses and to instil hope is to highlight and salute what can be achieved and changed through honest effort and creativity.

The loss of a friend may be one of the unavoidable wounds of life, but the memories of friendship remain an abiding treasure. And friends, therefore, live on, surviving in memories. And what is old, is new again.