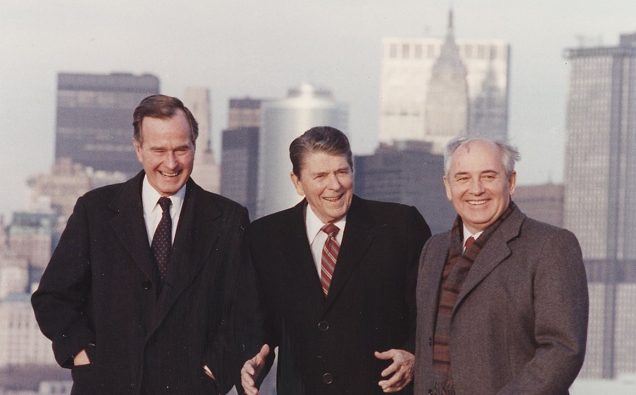

Featured Image President Reagan, VP Bush and Secretary General USSR Gorbachev Extracted from file on Wikimedia

The passing away of president George H.W. Bush provides a moment of reflection on the 1989 momentous turn of the history that will forever define his presidency – Soviet Union’s exit as a communist state in control of Eastern Europe and Central Asia, and the beginning of a new chapter of freedom for a large part of humanity. Bush’s deft approach to the historic event holds out instructive lessons.

1989 was one of the most pivotal years for South Asia – an end to the U.S.S.R. occupation of Afghanistan on Pakistan’s western border and the sudden flare-up of a militant uprising for freedom in Indian-controlled Kashmir on Pakistan’s eastern border.

The winds of change also began to sweep South Africa, where F.W. de Clerk, commenced his presidency that year – heralding a new time for the racially troubled country. The new president would oversee an end to the apartheid and release of Nelson Mandela from his long captivity.

Globally, the world said goodbye to one of the most dangerous periods, the Cold War, between the former Soviet Union and the United States. The two blocs were to dissolve into a new form with a new era of American leadership.

That time seemed to be a perfect phase in my learning – to explore and interpret developments unfolding on the international horizon. In 1989, I was a student of English Literature for my post-graduate degree and like my peers would often think many thoughts about the profession we would join for a bright future.

The last Soviet Union President Mikhail Gorbachev’s two books – Glasnost and Perestroika – were the hottest subjects in intellectual circles and the media during those years. The appearance of a series of articles in Dawn and The Nation newspapers provided much fodder for thought. Pakistani newspapers served the students and the nation well by focusing on the international developments.

So, I bought both the books and went through them as if I would die of hunger if I did not read them. This was the cusp of something huge – a turnaround or a turnabout in the modern history.

![Lear 21 at English Wikipedia [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1c/West_and_East_Germans_at_the_Brandenburg_Gate_in_1989.jpg)

Lear 21 at English Wikipedia [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

It was also a time of hope for Pakistanis as Benazir Bhutto had returned to the country from exile at the end of Zia ul Haq’s decade-long dictatorship, and contested in democratic elections. Pakistan was seen in a much better light internationally than it is now, an ally of the U.S. and the West for its role in the Soviet defeat in Afghanistan. So, the world looked full of new possibilities for the new generation of Pakistanis.

After about half a century of the Cold War – during which Pakistan had been under spotlight on several occasions including Pakistan’s joining CEATO and CENTO, U.S. spy plane U-2 flights from Peshawar on reconnaissance missions over Soviet Union, 1970s Richard Nixon reach out to China, and the 1980s U.S.-supported fight against Soviet occupation of Afghanistan – South Asia was wondering about what would happen next.

Will the world become unipolar? What will be the implications for India at the end of bipolar world as it depended so heavily on Soviet support? Will Pakistan remain as relevant and strategic to the U.S. interests?

The moment had both opportunities and perils. Celebration or chaos, what will follow? The world and Washington had to decide. All eyes were set on President George H W Bush as to how he would will handle the fall of the Berlin Wall, conclude the Cold War peacefully and help reunification of Germany.

And he negotiated the moment well – like a statesman – with care and diplomacy. When asked about his reaction to the November 9, 1989 fall of Berlin Wall, Bush replied:

“Well, I wouldn’t want to say this kind of development makes things move too quickly at all. I’m not going to hypothecate that it may. But we are handling it in a way not to give anybody a hard time. We’re saluting those who can move forward with democracy. We are encouraging the concept of a Europe whole and free. And so, we just welcome it.”

When journalists pressed a question about his feelings of joy on the occasion, he said.

“I’m elated. I’m just not an emotional kind of guy.”

If the U.S. president was seen as boasting of the West’s triumph over communist or socialist ideologies, it could have sent a spate of negative signals – it would have provoked defenders of communism and socialism to claim that the U.S. was interested only its victory and not the millions of East Europeans transitioning to a new undefined system. It would have given an excuse to agents of anarchy and chaos to kick up storms. It would have handicapped Gorbachev – the leader of change.

The fall of the Berlin Wall marked the collapse of the Iron Curtain, a description that Winston Churchill coined to define the metaphorical wall separating Eastern Europe from the West.

Bush, a representative of conservative values, had been prepared for this moment throughout his career. By serving in the U.S. Navy, CIA, the U.S. House, as US Ambassador to the UN and as two-time vice president under Ronald Reagan, he was well-qualified and trained to handle the moment. Just two years ago, Reagan had famously called on Gorbachev to “tear down this (Berlin) wall.”

With such a long career and commitment, Bush, in fact, had come to symbolize the American state – perhaps more than any other leader in recent history.

Bush, however, was not without faults. The U.S. involvement in the Gulf war after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, though successful from the American standpoint, also created massive problems for America’s image. Bush also faced criticism for being too official and staid in his speeches and was considered out of touch with people during election campaigns.

Yet, history will mention Bush more for negotiating the sensitive moment of modern history – a victory of the U.S. ideals of democracy and capitalism after a long Cold War competition and rivalry. That momentous moment set the tone for an unprecedented surge in U.S. influence over world happenings and continues to shape many contemporary events with the lesson that a U.S. retreat from the world stage – as partly practiced by both President Donald Trump and his predecessor Barack Obama – is not an option, and that in international diplomacy it is statesmanship that carries the day, not the rhetoric.