The United States prides itself on being a nation of immigrants, and the nation has a long history of attracting and successfully absorbing people from across the globe, and a new study finds that immigrants have continued to achieve the American Dream over the last century even under challenging times.

Contrary to commonly held perceptions, children of Mexican immigrants also have a much higher rate of succeeding and enjoying the promise of American ideals.

The successful integration of immigrants and their children into American society, in turn, contributes to economic vitality and to a vibrant and ever-changing culture.

It continues to happen as each year millions of immigrants come to the “New World” in the quest of an American promise of life, liberty and pursuit of happiness. Statistics say 41 million first-generation immigrants in the United States represent 13.1 percent of the U.S. population.

The U.S.-born children of immigrants; the second generation represents another 37.1 million people, or 12 percent of the population. The U.S. has more immigrants than any other country in the world, and this population of immigrants is also very diverse.

People from various parts of world come to United States and become a part of this “melting pot”, they all reach the shores with the dream of building a better life in this land of opportunity. Against insurmountable odds, language barriers and discrimination to name a few, immigrants flourish in the society and become a contributing arm of U.S. economy.

Immigration to United States has consistently provided immigrant families a great way to escape from poverty and/or persecution in their home world, which often is a reason for them to leave their countries.

The less privileged first-generation immigrants at times are not able to move up their economic status as fast as they would desire, but numerous studies have shown that their children i.e., the second-generation catches up to their native peers pretty fast and achieve their “American Dream”.

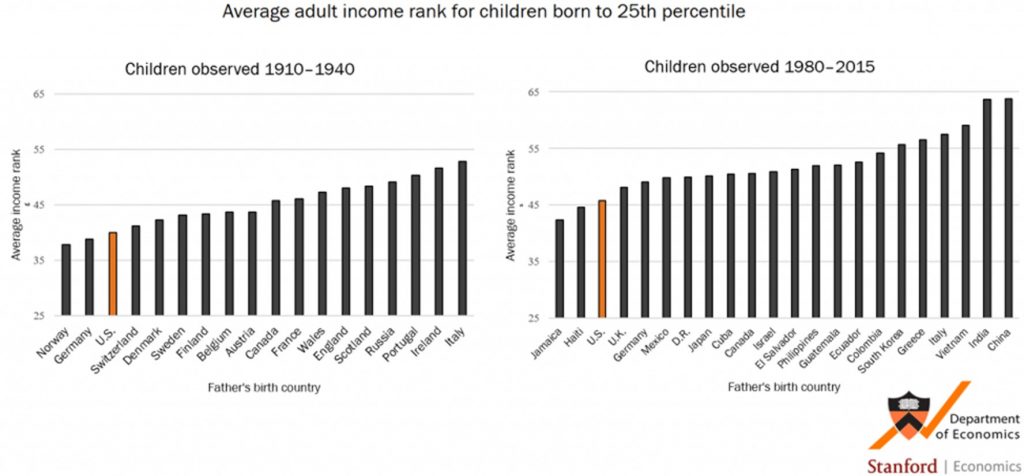

In the latest study recently released by Princeton, Stanford and the university of California, co-authored with Elisa Jácome of Princeton and Santiago Pérez of UC Davis find that children of poor immigrants in America have had greater success climbing the economic ladder than children of poor fathers born in the United States. Remarkably, this pattern has been stable for more than a century, even though the immigration laws have been changed over the course of time.

Using millions of father-son pairs from the poorest quartile across three different time periods, researchers shows that adult children of Poor Mexican and Dominican documented immigrants in the country today achieve same economic success as compared to children of poor immigrants from Finland or Scotland did a century ago. In both eras these children have done better than those born to US natives.

These findings also challenge the argument central to the debate over immigration in this government.

The Trump administration has introduced new immigration laws, which support wealthier immigrants. Arguing that nation can’t afford to welcome families who will burden public programs like Medicaid. Ran Abramitzky, a professor at Stanford and one of the paper’s authors, said that immigrants who arrive in poverty often escape it, if not in the first generation, then the second.

President Trump and advocates of tighter immigration have suggested that immigrants who come from Central America and Asia are less likely to assimilate in the society than earlier immigrants who were from Norway and other European countries.

But the analysis debunks this myth. In fact, going back in history, early Norwegians immigrants were among the least successful (economically) after they arrived.

The researchers also argue that politicians crafting immigration policy should not be so short-sighted. Immigrants who came to US with less resources or education bring something that is hugely beneficial to the U.S economy; their children.

Comparing three groups, from the 1880 and 1910 censuses and data from legal immigrants who first came to the U.S. around 1980, the study shows how children of first-generation immigrants growing up in the poorest 25 percent of the distribution end up near or in the middle class as adult. The study adds: these children of immigrants have rates of economic mobility that are 3-6 percentage points higher than their U.S. born peers.

For those in the top quarter of the income distribution, the gap in mobility is about 1-5 percentage points.

In many instances, language barriers, discrimination and limited job networks add to the challenges that new immigrant families face, but they march ahead against the sociopolitical and at times cultural headwind to plant their roots in this society and become part of American social fabric, and a key component of its economic success.

A very well written and articulate article.