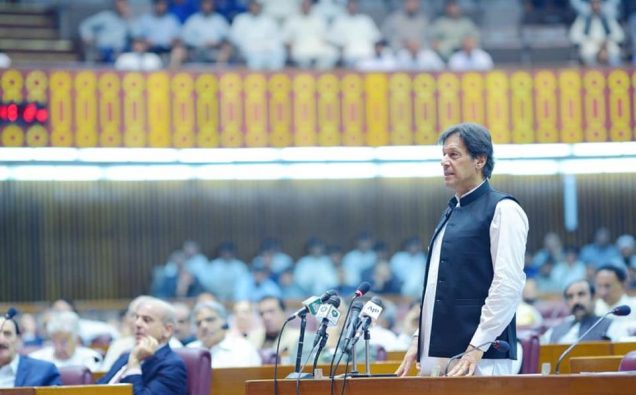

In dealing with the coronavirus outbreak, Prime Minister Imran Khan faces a huge challenge, which may prove to be even bigger than the dire economic conditions he inherited at the start of his government in 2018 summer.

For Pakistan, it is not simply a question of curbing the COVID-19 spread but how to accomplish such a mammoth task given poverty levels and absence of adequate medical services. Should Pakistan close its cities like the West? How should it ensure availability of preventive and medical supplies if the virus infects communities? How should it finance its fight against the disease? Khan has been staring at these choices and has at times appeared visibly undecided on picking between the stark choices.

Some of Khan’s dilemmas are understandable due to low socioeconomic indicators in a population of over 200 million and the nagging lack of access to healthcare in a large part of his country. If the coronavirus outbreak gets out of control, it would simply overwhelm the country. In other instances, his PTI government, which came into power on a wave of populist slogans, has not readied itself fast enough to deal with the unfolding crisis. The prime minister has ruled out shuttering down cities, saying a large majority of his countrymen can hardly afford to stay home as their livelihood depends on their going to work literally every day, without a fail.

But faced with calls to act urgently, he has directed a partial shutdown for a few days that include this weekend. The Opposition leaders, most notably, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari – son of late Benazir Bhutto – has called for a lockdown of the country. With the return of former government leader Shahbaz Sharif – who headed governance of Pakistan’s largest Punjab province – from London, pressure will likely further pile on Khan for some fast-paced and sweeping measures to stave off a COVID-19 catastrophe.

In an unprecedented peacetime move, Islamabad has halted all international flights into the country for two weeks. Pakistan International Airlines has announced suspension of all international flights until March 28. Pakistan has already closed its borders, albeit a little late. The earliest coronavirus infections were traced to Iran when a group of Pakistani pilgrims who contracted the virus in Iran brought them to the country on their return. The government has also faced criticism for not providing basic water and sanitation facilities to people quarantined on southwestern province Balochistan’s border with Iran.

Pakistanis tend to live in close proximity, often in large extended family or clan setups, and homes in cities are adjacent wall-to-wall, making the task of social distancing much harder. Even communities cannot stay away from one another. In majority of villages and towns, sanitary and health conditions are almost non-existent. The private hospitals have emerged in the last few decades but still cannot make up for the woeful absence of enough clinics and hospitals.

In the global context, the odds for Pakistan’s successful response sometimes appear overwhelming. If Iran in the neighbor and Italy and Spain, much richer European economies, cannot control the virus outbreak effectively, how can a developing country like Pakistan win the fight? The Chinese and South Korean examples also have a lot to do with economic prosperity.

Still, there are some things the Khan government can bank on in these trying times. Punjab, which houses more than half of the country’s population is agricultural heartland and has fewer reported infections – 152 out of 645 cases. If the government can work with civil society organizations, business leaders, local community and political leaders and volunteers including women and young people in raising awareness about the importance of social distancing and community safety, it would greatly help in curbing widespread cases. Secondly, the government can seek support from military. Sindh, the second largest province with the biggest cases of reported infections – 292 – has already requisitioned army support in its fight against the virus outbreak.

Thirdly, Pakistan can seek help from China to ensure medical supplies used in the treatment of patients. Beijing has already provided testing kits to the government, although it is not exactly known how the government is making use of them. But, almost perennially, it is the economics that would hurt Pakistan the most. With a load of external loan payments – like the IMF – and stagnation of exports, the major hope left is the remittances from expatriate Pakistanis. The government will need to have constant inflow of foreign exchange to meet the expenses. As a relief measure, Imran Khan has proposed a write-off of loans by the rich economies but there seems to be no immediate concession in sight as the U.S. and European countries are fighting their wars against the pandemic sweeping the globe.

The current scenario leaves lending institutions like IMF and World Bank and some of the Gulf nations for Pakistan to seek help from. The uncertain situation in Saudi Arabia may not be helpful. Faced with a mix of uncertain geopolitical dynamics and unfolding crisis, the best hope lies with the Pakistanis themselves. The Pakistanis are known for their resiliency on many turns of their history. But they need leadership to mobilize and find a direction. Can PM Khan or the combined national political leadership light a way out of the coronavirus outbreak? That question may very well determine the outcome of Pakistan’s fight against COVID-19.