When Friedrich Nietzsche ran to stop the brutal owner of a horse from thrashing it mercilessly in Turin, Italy, and threw his arms around the animal crying, “I understand your pain,” it gave us an extraordinary insight into his character and mind; more than his usually convoluted philosophic utterances. Nietzsche, who blithely declared to the world, “God is dead” could not bear the cruelty to the animal. While the image of Nietzsche is that of a world-class philosopher grappling with esoteric philosophic insights into the human condition and forever engulfed in controversy, this account reveals to us his sensitive nature that would have made the great Jain sage Mahavira proud. This episode also triggered his mental breakdown from which he never recovered.

Ten years later in 1900, after living in a vegetative state, he was dead. Ever since his breakdown he had been in the care of his sister. They had grown apart and had very different ideas about life and politics. She not only made her own edits to his work at will but after his death projected and distorted her brother’s thought in alignment with her own pro-Nazi and anti-Semitic prejudices. She had migrated to Paraguay to attempt to create a colony of like-minded right-wing Germans and falsified her brother’s ideas and ideology to curry favor with the Nazis. She even entirely fabricated numerous letters that she published in his name. This was morally reprehensible but she was doing thriving business in Nazi Germany. So impressed was Hitler by her loyalty that he attended her funeral. Nietzsche scholars have condemned her “criminally scandalous” forgeries (David Wroe, “‘Criminal’ manipulation of Nietzsche by sister to make him look anti-Semitic,” The Telegraph, January 19, 2010).Nietzsche’s Übermensch.

Nietzsche – A Mind like a Dark Cave

Nietzsche’s mind was like a vast, dark, and dangerous cave. In it dwelt flying creatures with sharp teeth. There were also those wondrous ones with luminous eyes conveying compassion and kindness. To enter the cave was an adventure and one never knew what would come flying at you. Take the matter of slavery. Nietzsche made several comments on slavery which are unacceptable to us. There is simply no excuse for the dreadful and disgusting institution of slavery. Nietzsche’s supporters cannot exonerate him by citing illustrious figures like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson and arguing that even the founding fathers of the greatest Western democracy owned slaves so the institution of slavery at that time was somehow excusable. They cannot also brush away this information because it comes in fragments from obscure notes of dubious sources and was perhaps influenced by his sister who was busy distorting his work over which he had little control. Nor can the supporters take his references to the Greeks whom he admired and argue that because they had slavery it was somehow acceptable. To me it is likely that Nietzsche’s fragments on slavery reflect his broader philosophy on the subject and he stands condemned. There is much to be explored and researched for the scholar in Nietzsche’s writing. But those entering the cave must do so with a strong torch and a stronger heart.

Nietzsche, Image: Friedrich Hartmann , Public Domain, wikimedia.

Nietzsche is without a doubt considered one of the greatest of Western philosophers and certainly one of the most controversial. From his bushy Groucho Marx mustache and eyebrows to his statement declaring God dead, Nietzsche seems to invite controversy and comment. One of Nietzsche’s concepts is that of the Übermensch, a superior man, a beyond man or superman who, through his being, justifies the very existence of the human race. It is one of his most famous, and in the wrong hands, as we will see below, notorious concepts. It comes from Nietzsche’s celebrated magnum opus, Thus Spake Zarathustra. In the novel, Zarathustra, the protagonist, retreats to the mountains at the age of thirty to seek knowledge and wisdom. Ten years later he has achieved his aim. His heart is overflowing with wisdom and love, like a bee with an abundance of honey, in Nietzsche’s words. He now wishes to share what he has gathered with humanity. On the way down from the mountain he meets an old man who predicts the people would not accept his message except with hatred and ridicule. People were miserable and although they lived in an advanced material society and indulged in base pleasures, they were still miserable. In spite of their condition, they rejected the wise man’s offer to share his wisdom. In the end they chased him away with their hatred and ridicule. Nietzsche, like the protagonist of the book, sets out to share his wisdom and love. And like the protagonist, Nietzsche also meets with ridicule and hatred.

The process whereby man progressed to Superman, according to Nietzsche, began with one’s will to do so. Between animal and Superman was man and man had to aspire to become Superman. To move beyond man, he had to aspire to the next stage of “creative evolution.” He was called the last man because that was the last stage before he could become Superman. It was different from Darwinian mutations and biological combinations with no aspirational aspects.

In terms of those people who had qualities of Superman, Nietzsche gave his own personal list. They included Goethe, Napoleon, Julius Caesar, Montaigne, and Voltaire. It is a list that most Europeans could identify with. Indeed, for Nietzsche, Goethe is probably the closest a human being can be to the idea of Superman.

The ideal qualities of the Superman, Nietzsche wrote, were “Caesar with Christ’s soul.” For those surprised to find Napoleon on the list, it is worth pointing out that others saw these figures as Superman too. For example, for Hegel, the eminent German philosopher, Napoleon was the very embodiment of the modern state and “the Absolute” or “the world-soul on horseback.” The Duke of Wellington famously said that Napoleon’s presence on the battlefield was the equivalent of 40,000 soldiers and a similar remark was made of Saladin, who we could call a Muslim Superman, at the time of the Crusades.

Examining the qualities of Nietzsche’s Supermen figures we may deduce some broad characteristics: they have a sense of destiny; something is driving them to spread their message and understanding to the world. They are generally protective of the weak and the vulnerable and concerned about the minorities. They are inclined to see the big picture and are not so concerned about minor things that may occupy other people. They are bold and independent in their thinking which often causes opposition and controversy. Their actions have an impact on distant places and into the future of which perhaps even they are not aware. Because they are extraordinary in their lives and aspirations, they are often lonely even though surrounded by followers and admirers. They find followers rather than companions. They often spend time by themselves, retreating to isolated caves and mountains. They are brilliant in their strategic choices and moves. They are not always successful and since they are creating new ideas and challenging old ones, they often suffer a backlash that may even cost them their lives in the process. Even after they die, they cross time and space and remain alive in the imagination of their followers. As Nietzsche’s list of his own figures who approached and approximated the Superman is subjective and personal, each one of us is entitled to drawing up our own list. It is an exercise to be recommended as it will tell us as much about ourselves as our society.

When Nietzsche’s Zarathustra went up the mountain seeking a species of Superman, he did not quite appreciate that they were in plain sight all along. Indeed, the concept of the Superman is not new. We have examples from the past going back several thousand years of figures who could justifiably be called Superman, from Moses, who parted the sea, turned his staff into a snake that ate up the Pharaoh’s snake, and climbed a mountain to talk to God, to Jesus Christ, who walked on water and gave life to a corpse. There are other figures such as the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II who brought the different religions and communities in his empire closer together through scholarship and in mutual respect. In Hindu mythology we have examples of ancient heroes performing superhuman feats. Most societies have their own towering figures that they view as supermen—or superwomen. So, while among Christians, Jesus is the ultimate Superman, among Hindus it is Lord Ram, among Buddhists Lord Buddha, and so on. Plato’s philosopher-king was a prototype Superman and Alexander the Great was seen as an early Greek version of the Superman. Earlier in Nietzsche’s century, Thomas Carlyle had written his celebrated On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History which was similar in scope to Nietzsche’s Superman idea and included several figures such as the Prophet of Islam, Rousseau and Napoleon that could over-lap with those on Nietzsche’s own list.

“Insan-i Kamil”: The Prophet as the Muslim Superman

For Muslims, the figure of the Superman is represented by the Prophet of Islam. The Quran stated that God created man to be God’s vicegerent on earth; a super superman if you will. The high status and expectations of man are inherent in Islam’s theological vision and philosophic understanding of the nature of man. That philosophic vision is suffused with the notions of compassion and mercy. This potential in man finds its ultimate expression in the Prophet of Islam, the model and example for Muslims to aspire to. God’s greatest attributes are derived from his two most popular names—Rahman and Rahim—Compassionate and Merciful and as he is the Messenger of God the Prophet is described in the Quran as a “mercy unto mankind.” The Prophet is known in the Islamic tradition as Insan-i Kamil or the Perfect Man, the equivalent of the Superman, and he is also called Khayr ul Bashr, or the best of mankind.

There are indeed interesting parallels between Nietzsche’s Superman and the Perfect Man in the Islamic tradition as personified by the Prophet. Is there a more direct relationship between the two concepts? Did the way that Muslims conceive of the Prophet of Islam, in turn, influence the construct of Ubermensch or the Superman? If so what are the intellectual links to possible sources that we can trace? The clues are many although some are admittedly weak. Yet it is worth exploring some of the connections which may heighten our understanding of both concepts and their similarities.

Goethe Image: By Joseph Karl Stieler / Wikimedia

Nietzsche may have been consciously or unconsciously influenced by the Islamic notion of the Perfect Man through sources such as Goethe, his number one exemplary role model for Superman. While Goethe wrote his devotional poem in honor of the Prophet called “Mahomet’s Song” at the age of 23, at age 70 he publicly declared he was considering “devoutly celebrating that holy night in which the Quran in its entirety was revealed to the prophet from on high.” Goethe’s comments on Islam have led to speculation about the extent of his commitment to the faith, for example, in the following verse: “If Islam means, to God devoted/ All live and die in Islam’s ways.” In fact, Goethe himself sometimes wondered if he was actually living the life of a Muslim, writing, when announcing the publication of his poetic work West-Eastern Divan, that the author “does not reject the suspicion that he may himself be a Muslim.”

No Muslim can be unmoved by Goethe’s poem, “Mahomet’s Song,” dedicated to the Prophet of Islam, whom he calls “chief” and “head of created beings.” Goethe had intended to write a longer piece in which Hazrat Ali, the cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet and himself a Superman figure as a great scholar and warrior, was to have sung the poem “in honor of his master,” but the project was never completed. “Mahomet’s Song” is a powerful expression of the desire to discover unity in the universe while searching for the divine. Goethe uses the metaphor of an irresistible stream that flows down from the mountains to the ocean, taking other streams along with it. Here are some verses from the poem:

“And the streamlets from the mountain,

Shout with joy, exclaiming: ‘Brother,

Brother, take thy brethren with thee,

With thee to thine aged father,

To the everlasting ocean,

Who, with arms outstretching far,

Waiteth for us…

And the meadow

In his breath finds life.’”

Nietzsche followed Goethe in his admiration for the Prophet of Islam. Nietzsche compared the Prophet to Plato, one of the foundational figures of Western civilization. For Nietzsche, Plato “thought he could do for all the Greeks what Muhammad did later for his Arabs.” Muslims, who have been fascinated by Greek philosophers like Plato, have invariably seen the Prophet of Islam as the philosopher-king that Plato dreamed of and the Muslim community, as in the example of the early settlement in Medina, as the realization of Plato’s ideal City. Nietzsche also followed Goethe in his admiration for the great Persian poet Hafiz. Nietzsche wrote a poem extolling the heroic virtues of Hafiz including the fact that Hafiz was a “water drinker”—along with Christianity the drinking of alcohol was one of Nietzsche’s bugaboos about Europe. In Thus Spake Zarathustra, Zarathustra is referred to as “a born water drinker.” The poem Nietzsche wrote in honor of Hafiz is entitled “To Hafiz: Questions of a Water Drinker.” It is worth reminding the reader that Islam forbids the drinking of alcohol and Muslims are thus quintessential water drinkers.

In spite of the potential for research, the interest in Islam of Goethe and Nietzsche has been relatively unexplored and even neglected. There are many dissertations waiting for the diligent researcher in this field. Most Germans, who acknowledge Goethe as the Shakespeare of the German language and the classic Renaissance man, do not know about Goethe’s enthusiasm for Islam, which lasted his entire life. Bekir Alboğa, the secretary general of Germany’s largest Islamic organization, the Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs (DITIB), when interviewed for my project Journey into Europe in Cologne, described Goethe as “a brother to me,” and “a great thinker with a great affinity for Islam.” Goethe “wrote a wonderful poem about our Prophet,” he said, referring to “Mahomet’s Song.” Alboğa complained that in Germany the Islamic dimension of Goethe’s work is ignored, if not intentionally suppressed. As for the subject of Nietzsche and Islam that too remains largely uncharted territory. (For a detailed discussion of attitudes to Muslims in contemporary Europe see my book Journey into Europe: Islam, Immigration and Identity, 2018).

Nietzsche, Islam, and Christianity

We have further interesting connections in the relationship of Nietzsche to Islam. Like other German philosophers such as Hegel and Goethe, Nietzsche too sought to understand the meaning of life and the place of the human in existence. The ultimate aim was to discover the path to a fulfilled and even contented life. In the process, like the other philosophers, Nietzsche found himself highly critical of the philosophic and ideological structures that dominated Europe and blamed them for the misery of ordinary people. Nietzsche therefore attacked the Christian church and the state. To him, both were sources of oppression. The church had failed to provide happiness on earth to its followers and therefore its rituals were meaningless. While Christians outwardly acted out the rituals of Christianity and religion, they had lost their conviction in the faith. It was this context that prompted Nietzsche to pronounce the sentence that gave him instant notoriety declaring the death of God. As for the state, Nietzsche was an early critic of Otto Von Bismarck, the architect of the German state, which would go on to become the embodiment of the modern state. Nietzsche warned of the centralizing and tyrannizing tendencies of the state which inevitably would show hostility towards ethnic minorities. Nietzsche the philosopher was an iconoclast: both church and state were corrupt and corrupting. In this sense, Nietzsche was ahead of his time and even predicted what was to come in Europe.

Nietzsche attempted to fill the vacuum by arguing for the ideal of Superman. For him, wisdom and love are key to understanding Superman. When a person realizes their human potential and fulfills it, they are able to move away from the “herd morality” of Christianity and religion to become a Superman. It is noteworthy and could strike the uninitiated as eccentric, that while dismissing Christianity, Nietzsche appears to be constantly praising Islam. For Nietzsche, Christianity and Islam have a perverse relationship in the sense that while he demeans and shows contempt for the former, he turns towards the latter and elevates it. It is a tension within Nietzsche that is not resolved.

For Nietzsche, Muslims are noble and he describes them as “manly,” “life-affirming,” and “honest” (the first adjective is from his 1895 book The Antichrist). Nietzsche even points to the “warlike” qualities in Islam. In fact, there are over 100 references to Islam in Nietzsche’s work. Islam is simply everything that Christianity is not. He is so enamored of Muslims that in a letter to a friend he ponders relocating to Muslim lands in North Africa. The scholar Ian Almond wrote, “it is difficult to resist the tempting hypothesis: that had Nietzsche’s breakdown not been imminent, we would have seen a work dedicated to Islam from his own pen” (“Nietzsche’s Peace with Islam: My Enemy’s Enemy is my Friend,” German Life and Letters, 56:1, January 2003, p. 51).

Nietzsche blamed Christianity in The Antichrist for the elimination of the advanced civilization of Muslim Spain and the Crusades: “Christianity destroyed for us the whole harvest of ancient civilization, and later it also destroyed for us the whole harvest of Mohammedan civilization. The wonderful culture of the Moors in Spain, which was fundamentally nearer to us and appealed more to our senses and tastes than that of Rome and Greece, was trampled down.” If there is any doubt as to his position regarding the two religions, Nietzsche himself dispelled it in The Antichrist: “There should be no choice in the matter when faced with Islam and Christianity. War to the knife with Rome! Peace and friendship with Islam!”

There are also parallels in the manner in which the idea of Superman is revealed in Thus Spake Zarathustra and the history of early Islam. As in the case of the Prophet, Nietzsche’s protagonist in Thus Spake Zarathustra ascends a mountain, acquires knowledge at the age of 40—the age at which the Prophet received his Quranic revelation—and comes down from the mountain with wisdom and love to share and faces hostility and cynicism. In fact, this pattern reflects not only the broad outline of the early days of Islam but that of many Biblical prophets.

It is worth noting that two of Nietzsche’s Supermen, Goethe as well as Napoleon, expressed their admiration for Islam. Napoleon in Cairo dressed in Arab robes, spent time with Sheikhs from Al Azhar, said he had become a Muslim, and even took a Muslim name. Nietzsche, like Wagner, also praised the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, calling him a “genius” and celebrating the fact that he fought the papacy while seeking “peace and friendship” with Islam.

This raises the question as to why Islam impresses Nietzsche so much. I have explored the answer at some length in my book Journey into Europe in which I argued that traditionally some European scholars and philosophers cast Islam and its tribes in the classic romantic mold of Rousseau’s “noble savage.” To them the Muslim tribesman, the Berber in the deserts, or the Pashtun in the mountains, had escaped the deprivations of modernity and preserved their natural and original nobility. This was particularly true of German scholars, who, as I explain in Journey into Europe, thought of themselves as belonging to a kind of tribal society going back to Germany’s status as the frontier of the Roman Empire and celebrated the work of Tacitus who wrote of the German tribes of that time. Thus, German scholars were more likely to respect other societies that they deemed worthy and had characteristics that reflected German self-perception. They increasingly set the German people, ethnicity, language, and religious interpretation against the central authority of the Catholic Church based in Rome in forging a distinct German identity and often displayed a concurrent fascination and appreciation for Islam and Islamic culture. Figures like Dürer, Goethe, Wagner, and Nietzsche reflected this larger world-view, which I called the historical German “soft spot” for Islam.

Nietzsche was thus a genuine admirer of a civilization that he knew very little of. In the nineteenth century Islam was going through a difficult period of its history and it had not yet emerged from colonization. It was dominated by often ignorant and decadent rulers and there was chaos and corruption in its societies. Yet Nietzsche and many others romanticized it seeing instead the uncorrupted noble savage. Through such Orientalist eyes the Islamic world though seen as barbarous and anti-modern was yet a praiseworthy society. We see this tendency continuing in Europe as modernity developed into the next century. By the time of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World written some 30 years after Nietzsche died, the most “normal” character is John who is widely called a “savage” and lives outside the bounds of the totalitarian World State.

Nietzsche and Iqbal

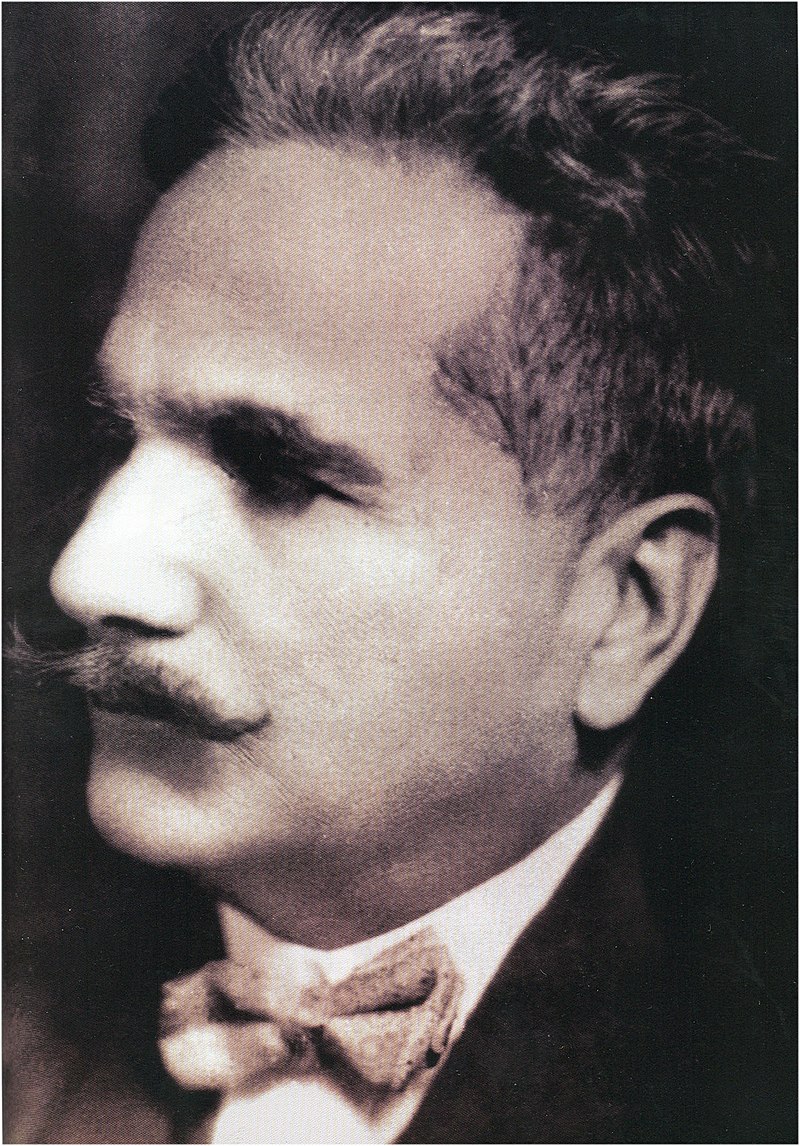

Perhaps the most celebrated direct relationship of the concept of the Insan-i Kamil or the Perfect Man and the Prophet to Nietzsche was highlighted by Allama Muhammad Iqbal, the revered “Poet of the East.” Iqbal had arrived from British India for his studies at Cambridge University where he was enrolled at Trinity College, after Nietzsche died in 1900. A brilliant student of philosophy, Iqbal very quickly absorbed the leading philosophers of the time including Nietzsche.

Iqbal’s own work reflected Nietzsche, albeit with a more religious dimension linked to Islam, to the extent that he was accused of plagiarism, a charge that has stayed with him long after his death. Iqbal believed that through the understanding of religion, Man could develop his potential to become the Perfect Man, in short Superman—a Superman whose mind ranged across the cosmos: “Sitaron sey aagey jehan aur bhi hein!/ Abhi ishq key imtihan aur bhi hein” –“There are many worlds beyond the stars!/ And many more tests of love”.

Iqbal notes that God himself in the Quran made man in the image of the divine as a vicegerent on earth, a phrase used in the Quran. Man could aspire to the heights set by the Perfect Man, the model of the Prophet, and Iqbal exhorted his readers to do so. We see the religious dimension in Iqbal’s understanding of self-betterment in the last lines of what is Iqbal’s arguably most famous populist poems, “The Complaint” and “The Answer to the Complaint.” The latter poem has God clearly informing man in the last verses that as long as he is faithful to the Prophet of Islam then everything belongs to him. “Ki Muhammad say wafa tu nay to hum teray hain/ Ye jahan cheese hay kia luh o kalam teray hain”—“If you are faithful to Muhammad, than I am yours./ Why do you ask for this universe? I will give you the secret to knowledge.” Iqbal thus acknowledged the legitimacy of Superman while also his connection to God. Whatever Nietzsche thinks of the matter, for Iqbal man cannot break that link from and to God.

Iqbal acknowledged Nietzsche in his short poem “Hakeem Nietzsche” or “Learned Sage Nietzsche” and mentioned him in his celebrated poetic work Payam e Mashriq or “Message of the East” (1923), a response to Goethe’s West-Eastern Divan. About Nietzsche Iqbal sighed, “His heart is that of a believer’s but his brain that of an infidel’s.” For Nietzsche, religion represented the “herd mentality” and needed to be rejected. For Iqbal, religion was the door to explore the mysteries of the universe and man’s place in it, thereby finding salvation. While the thrust of Nietzsche’s thinking is to attack the structure and thought of Christianity, and thereby implicitly the notion of God, Iqbal is moving in the opposite direction.

Sign for the street Iqbal-Ufer in Heidelberg, Germany, honoring Iqbal Image: By Smasahab / Wikimedia

Although Iqbal had been intellectually engaging with Western philosophers like Goethe, his tone with Nietzsche was different to the one he used for Goethe. Nietzsche’s lack of spirituality for Iqbal casts the German outside the pale. Iqbal is almost cruel in his denunciation of Nietzsche. He accuses Nietzsche of plunging a dagger into the heart of the West and says that his hands were soaked with Christ’s blood. Had Nietzsche been alive, Iqbal wrote, I would have taught him how to be a decent and moral person.

There was another dimension to the relationship between the two philosophers. The charge that Iqbal’s thought was too close to Nietzsche’s for comfort could have accounted for Iqbal’s bitterness towards Nietzsche. It was as if he was somewhat wary of him and was attempting to push him away. Perhaps Iqbal was sensitive to critics suggesting he had borrowed the concept of the Superman to create the concept of the Perfect Man. Iqbal went to great lengths to distinguish his concept of the Perfect Man from that of Nietzsche’s Superman. Iqbal stated emphatically, “I wrote on the Sufi doctrine of the Perfect Man more than twenty years ago, long before I had read or heard anything of Nietzsche.” His Perfect Man could not be perfect without a strong spiritual component.

Still, commentators picked up the similarities. We see this in wide-ranging commentary from the novelist E. M. Forster’s review of Iqbal’s Asrar-e-Khadi, “Secrets of the Self,” in 1920 to Omer Ghazi who in 2018, ignoring the high respect Iqbal enjoys in Pakistan as the national poet, used a scattershot approach to accuse Iqbal of virtually everything under the sun: “his poetry is filled with racism, anti-semitism, jingoism, communal hatred, hyper-nationalism, religious fanaticism, anti-intellectualism and calls for bloodshed.” The title of Ghazi’s article, published in Heartland Analyst, was “Why Allama Iqbal needs to be condemned, not celebrated.” In the long list of items that deserve condemnation, the author claims, “Iqbal later plagiarized his whole idea of Mard-e-Momin [the Perfect Man] from the philosophy of Ubermensch put forth by the same Western Madman decades ago.”

Forster in his review was less direct, hinting in his typically cultured way, that Iqbal may have taken his concept of the Perfect Man from Nietzsche while acknowledging Iqbal’s “tremendous name among our fellow citizens, the Muslims of India.” “What is so interesting,” Forster writes of Iqbal, “is the connection that he has effected between Nietzsche and the Quran. It is not an arbitrary or fantastic connection; make Nietzsche believe in God, and a bridge can be thrown.”

Forster’s discussion of Iqbal here fits in to his larger pattern of treating Muslims with affection, even with reverence. Whether describing the Mughal emperor Babar or Sir Ross Masood, the grandson of Sir Syed Ahmed, to whom he dedicated one of his most popular novels, A Passage to India, or indeed the lead character in that novel, Dr. Aziz, his affection for Muslims is apparent.

For me, the argument of who first discovered the concept of a Superman or Perfect Man is really a non-argument. It is perhaps the concept and title of Superman that really catches the imagination. Neither Nietzsche’s Superman nor Iqbal’s Perfect Man are original concepts. There is a long list of supermen in Western culture that Nietzsche would have known of, as noted above. As for Iqbal, his concept of the Mard-e-Momin or the Insan-i Kamil is a concept deeply embedded in Islamic literature and Iqbal himself refers to Rumi and other mystics who write of the Insan-i Kamil. From the very origins of Islam, the Prophet of Islam has been cast in the mold of the Insan-i Kamil. Indeed, it has been the ambition of every great Muslim poet to write a tribute to the Prophet in precisely these terms.

Nietzsche’s declaration that God was dead was also not entirely original. European philosophers had been arguing for the supremacy of science without which they felt there could be no progress and therefore they needed to put away the idea of God. In effect Marx had already pronounced God dead when he declared religion to be the “opium of the people.” Darwin had posed a secular and godless explanation for evolution and before him Napoleon had indicated he did not believe in a specific God though in a general sense he went along with spirituality. While Nietzsche’s declaration that God was dead was not entirely original, what is interesting is his suggestion of taking the blame in his use of “we” for the death of God in his following sentence, “and we have killed him”.… he has “bled to death under our knives.” Indeed Nietzsche describes God, which in this context would also include Jesus Christ, as the “holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned.” This hints at a certain guilty sentimentality for killing off God that has perhaps escaped his critics. While Nietzsche constantly attacks Christianity, his respect for Jesus is clear, as seen in his statement published in The Will to Power, “What is wrong with Christianity is that it refrains from doing all those things that Christ commanded should be done.”

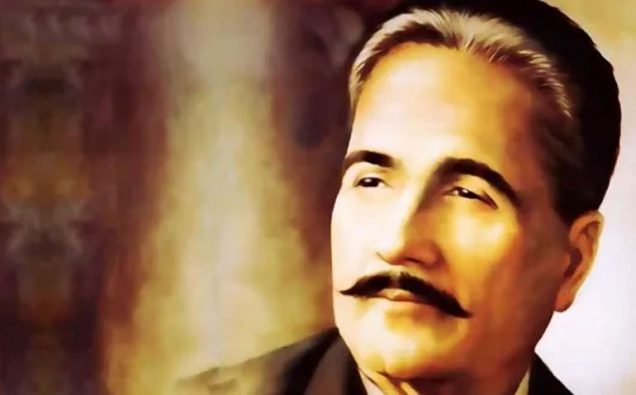

Muhammad Iqbal Image: By Iqbal Academy Pakistan

If my premise is correct that Nietzsche may have consciously or subconsciously borrowed aspects of his Superman from the notion of the Perfect Man through sources like Goethe then it changes the nature of the debate between Iqbal and Nietzsche. Iqbal wants to pull the German closer to Islam; but Nietzsche is not really resisting. He has declared that God is dead but at the same time he is constantly praising Islam and at the center of Islam is the notion of God and the Prophet of Islam; together they form the primary declaration of the Islamic faith.

Iqbal’s treatment of Nietzsche raises some pertinent questions which lie beyond the scope of this article. The first question is: are only faithful and practicing Muslims eligible to become Perfect Man? Nietzsche’s own concept of Superman had no such restrictions. Why did Iqbal fail to see the yearning for Islam in Nietzsche? Was it a methodological failure or mere human petulance?

Nietzsche’s Legacy

It is Nietzsche’s misfortune that in a profound sense his reputation was compromised by the admiration Hitler and the Nazis had for him. Ironically Nietzsche was long dead when Hitler came to power; his mental collapse began the year Hitler was born in 1889. In any case, Nietzsche’s aversion to the Nazi kind of mentality was well known and is explicit in his work. Nietzsche’s philosophic position was diametrically opposed to the rigid certainties of the Nazis. Nietzsche’s ideas, like “the will to power,” make abundantly clear he rejects “certainties” and “absolutes” while emphasizing his ideas were merely “interpretations.” As he lay stricken in bed in a state of mental collapse it was his sister who successfully projected him as a Nazi sympathizer by distorting his image. Hitler even visited the museum she ran in her brother’s name and photographs were taken of the occasion. By attending her funeral Hitler consolidated the status of her brother as a German icon in the Nazi era; it also forever damned Nietzsche in the eyes of those who loathed Hitler. It was difficult to reconcile the man on the mountain in Thus Spake Zarathustra who had gathered love and wisdom to share with humanity with the vile philosophy of hatred and violence promoted by the evil ideology of the Nazis.

In spite of Hitler and the Nazis embracing it enthusiastically, the concept of the Superman, as we have seen, is not that of hard-eyed and chiseled-jawed muscular young men in jackboots searching for members of the minority, but one of self-fulfillment and betterment. Decades after Nietzsche’s death, it was the word—Superman—that to the arrogant Nazis seemed to fit like a glove in their demented dreams of world conquest and racial superiority.

It is interesting in the context of what transpired in Europe in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries to examine some of Nietzsche’s warnings for us that resulted in his promotion of Superman. He had warned against the state that takes the place of God as it will enslave us. It was “the coldest of cold monsters.” Remarkably he predicted the rise of the socialist centralized states and the violence that they would create. Nietzsche saw Bismarck’s vulgar “blood and soil” politics as a harbinger of things to come. He condemned the Prussian statesman who unified Germany in 1871 for cementing his power by stoking nationalist resentments and appealing to racial purity.

It was the beginning of a period of great transformation in Europe. There was a debate about the future of the continent, and Nietzsche perceived a shift into a form of “petty politics” of the sort pioneered by Bismarck. Nietzsche hoped for a grand unification of Europe, a transnational politics in which high culture and art could thrive. What he witnessed instead was more fragmentation, more nationalism, more tribalism. Nietzsche developed frameworks to analyze these transformations that could help us think differently about the unraveling we are seeing today in Europe and North America.

Nietzsche’s influence has been, and remains, far and wide. Intellectuals have written about Superman, for example George Bernard Shaw in his 1903 play Man and Superman. In the 1930s two young American Jewish men with an East European background created the comic book character Superman who went on to become one of the most successful comic book characters of all time. This Superman wore the colors of the United States, red and blue, and like the nation was the champion of justice and fair play. He was described as, “Faster than a speeding bullet! More powerful than a locomotive! Able to leap tall buildings at a single bound.” Two other young American men, Leopold and Loeb, who in the 1920s planned the “perfect crime” by murdering a younger weaker boy in Chicago to establish their superiority, Jack Kerouac, who mentions Nietzsche in the first paragraph of On the Road, and Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, the American professor who in 2012 produced an academic book, American Nietzsche, which dramatically recasts our understanding of American intellectual life and puts Nietzsche squarely at its heart, were all in one way or another influenced by Nietzsche. Mom, the American TV series, had an episode called “Nietzsche and a Beer Run” featuring a romance with a muscular fireman who has a Ph.D in philosophy and the heroine. I was struck by Nietzsche’s entry into American pop culture even though there was the underlying running joke of the improbability of a philosopher as a hot fireman. Luc Ferry has been in the forefront of French scholars in engaging with Nietzsche and attempting to contain his influence on French philosophers. Their efforts are framed in philosophic terms: “To think with Nietzsche against Nietzsche.”

Perhaps the best methodological approach to the discussion of Superman is not to be distracted either by abstruse philosophic debates or to see him in relation to the DC Comics hero but instead to return to Nietzsche. His aim was to urge mankind to become the best that we as human beings can aspire to, the finest, ultimate version of ourselves. Superman is something that is within us and something that we in the future can become.

The Superman in the Age of the Pandemic

We are now confronted with a serious crisis in the coronavirus pandemic which has attacked humanity. I believe that in this environment we need to remind ourselves of the concept of Superman which gives us an important perspective and tools we may use to rise to meet the current challenge. It also provides us with a kind of model of leadership we need.

Having rejected the tyrants of the twentieth century, the Hitlers and Stalins, why should mankind turn to Superman now? Let us look at the United States, the most powerful and economically prosperous nation in the world when the pandemic hit early in 2020. It is well to keep in mind that one American is dying every minute of the virus, around a thousand Americans are dying daily, and as of writing this piece in mid-August there are about five million cases and over 160,000 have lost their lives. So far, no vaccine has been discovered.

But we do not need Superman to work in the laboratory as a medical researcher. We need Supermen because we wish the wise and the compassionate to guide us in these terrible times, to give us hope as we know they transcend ordinary politics. They are especially needed as symbols because traditional leadership has proven a dangerous failure. People are disillusioned by their leaders who they see as out of touch, corrupt and incompetent. We need them as studies show the majority of people, in America, for example, are suffering from mental health problems such as depression and thoughts of suicide. The pandemic has made people short-tempered and easily angry; it has promoted violence. Societies desperately need figures that are unimpeachable and can unite and inspire. People seek compassion and wisdom.

Discarding ideas of the stereotypical Superman as a muscular bodybuilder, we have some remarkable candidates in our own age. These would approximate to the classic definition of Superman as laid out by Nietzsche. We have President Jimmy Carter, the late John Lewis, and the current chief medical advisor to the US government, Dr. Anthony Fauci to name three. Each one of them in their own way has contributed to society and helped make it better, aspiring towards something beyond itself. Each one of them faced challenges and resistance. But in spite of the hurdles, they faced they provided moral clarity, moral leadership, and an example that brings out the better angels in us. In that sense, they are aspirational figures. There are also public intellectuals whose reach extends beyond the borders of their countries—Professors Rajmohan Gandhi in India, Noam Chomsky in the United States, and Dr. Haris Silajdzic in Bosnia-Herzegovina, for examples. There are outstanding religious figures: in the United Kingdom, we have figures like Dr. Rowan Williams and Lord George Carey, both former Archbishops of Canterbury, and Lord Jonathan Sacks, the former Chief Rabbi of the UK, and in Eastern Europe, there is the former Grand Mufti of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Dr. Mustafa Ceric.

During the pandemic, we have seen a tendency for large sections of society to fall back to traditional faith. It gives them a sense of belonging, a feeling of being part of a bigger family and a community and it also provides certainty in an uncertain time. It provides this even when miracles do not happen and those who fall ill and even die cannot avert the disaster by prayer alone. In spite of the limitations of religion to perform miracles, people still cling to what is familiar and it gives them comfort. In the same way, the Superman idea allows communities to look up to its leaders and be inspired by them. The problem is that we live in an age where nothing is hidden or kept secret for long so that no leader, however retiring or modest, can escape the destructive attention of the media. Sooner or later the searing cynicism of the media and its iconoclastic eye will spot the weaknesses in individuals and then proceed to tear down those it may have built up only recently. That is why Superman today would find it very difficult to remain a Superman and our own choices indicate how difficult it is for Superman to survive.

While the fact that Brad Pitt, one of Hollywood’s most glamorous stars, played Dr. Fauci confirms the good doctor’s popularity in American contemporary mythology, Fauci is also not only attacked by those on the right but by Donald Trump, the president of the US himself. This has generated an avalanche of hatred against Fauci and he has had to hire security to protect himself and his family. That hostility is the fate of Nietzsche’s Superman. It is also a fact that when this ugly Covid-19 virus finally lifts, and with it the current crop of so-called leaders who stand exposed as hollow and corrupt, societies will desperately need to turn to those they can trust for guidance and wisdom. Perhaps then it may be the time of Superman.