By Akbar Ahmed and Brian Frost

On December 26, we lost two icons of enlightenment: Nobel peace laureate Desmond Tutu and two-time Pulitzer Prize recipient, biology professor E. O. Wilson (there is no Nobel award for biology). We were saddened, as citizens of the world and as colleagues, to learn of the loss of these two men, both of whom contributed powerful essays to a book we edited in 2005. It turns out that they are more deeply connected than just by the coincidence of their passing on the same day.

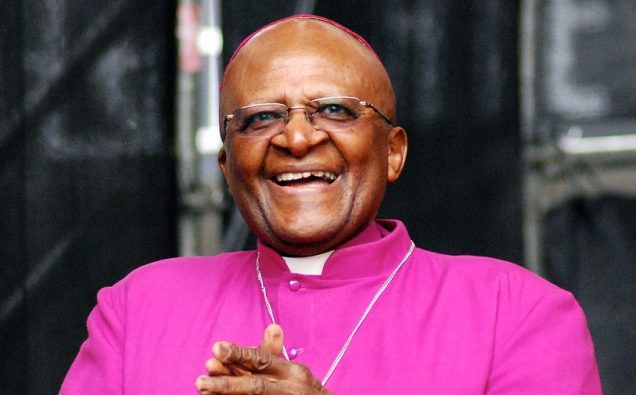

They were different in a fundamental way — Tutu found his core truths in God; Wilson found his in science. And in other ways too: Tutu was charismatic and boyishly cheerful; Wilson was more understated and ironic. But they shared important traits: Both were gifted leaders in their respective fields. Both were eloquent, and very funny too. Both wrote on the power of cooperation to build a vibrant society. And both were extremely consequential in their fields and well beyond. Both men advanced humankind in significant ways.

Although just five-foot-four, Archbishop Tutu was a moral giant. He wrote that religion is a two-edged sword: healthy when transcendent and malignant when caught up in finding infidels and adversaries. He observed that all religions emphasize fundamental moral values of honesty, compassion, fidelity in marriage, the unity of humankind, and peace, but that religions have too often produced rogues who hijack the faith for selfish ends.

Professor E. O. Wilson was no less consequential in the domain of science. Widely regarded as the father of biodiversity and sociobiology, he pioneered the study of nature’s role in shaping human behavior. His research spanned the spectrum from specialist to generalist on a grand scale, starting with his path-breaking research on ants and moving eventually to the biological basis of morality and an overarching theory of consilience in the natural world. His 1975 book, Sociobiology, not only created a stir in describing evolutionary forces behind social characteristics of organisms but also spawned the field of evolutionary psychology in the 1990s. He argued compellingly that the spiritual impulse is both an evolutionary advantage central to human nature and a key to hope for the future.

Their similarities became abundantly clear to us when they responded in much the same way to the question we asked them in 2004, in the shadow of 9/11: What can we do to prevent further acts of terror? Both Tutu and Wilson argued that organized religion does too little to discourage violence in the name of God. Tutu wrote this, in his chapter, “God’s Word and World Politics”: “All faiths teach that this is a moral universe. Evil injustice and oppression can never have the last word. Right, goodness, love, laughter, caring, sharing and compassion, peace and reconciliation, will prevail over their ghastly counterparts. The powerful unjust ones who throw their weight about, who think that might is right, will bite the dust and get their comeuppance.”

Wilson was somewhat less optimistic than Tutu. While he argued that spirituality gives humans an evolutionary edge over other species, he was less sympathetic to the institution of religion: “Religion divides, science unites … Because scientific knowledge is instrumental and objective in origin, as well as transparent and replicable, it transcends cultural differences.” Wilson granted that religion has enriched cultures with some of their best attributes, including the ideals of altruism, public service, and aesthetics in the arts, but added that it has also validated tribal myths that are “forever and dangerously divisive.” Noting caustically that the sacred texts of the Abrahamic faiths speak on behalf of “archaic patriarchies in the parched Middle East,” he saw that scientific illuminations of enlightened people offer a more transparent and reliable basis for understanding, in a manner that transcends cultural difference and unites humanity. Religion may have given humans a Darwinian edge in earlier times, he wrote, but rational thinking and proven knowledge should give humans the edge today.

In their final years, both Tutu and Wilson expressed concerns that we are falling from a trajectory of enlightened thinking, with tribalism on the rise. But their writings have profound implications for organized religion to take much more robust stands against violence today in India, Europe, the United States, and elsewhere. Neither man retreated from the expectation that our better angels will eventually prevail, that today’s clerics at all rungs of religious hierarchies may wish not to repeat sins of the past. Tutu: “Hope is being able to see that there is light despite all of the darkness.”

Rest in peace Desmond Tutu and E. O. Wilson. You have left us gifts for eternity.

ABOUT AUTHORS

Akbar Ahmed is the Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies and Professor of International Relations at the American University in Washington, DC.

Brian Forst is Professor of Justice, Law, and Criminology emeritus at the American University School of Public Affairs. They co-edited the book, After Terror (Polity, 2005).