Pakistani-American author Abul Hasan Naghmi, who passed away this week at the age of 92, was an illustrious immigrant. He came to the United States as a broadcaster to work for the Voice of America in the 1970s, and alongside his peers, contributed significantly to the growth of Urdu journalism.

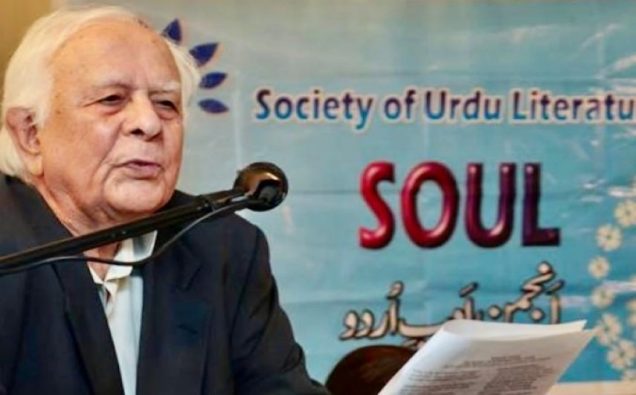

However, for the growing South Asian communities in the 21st century, Naghmi’s name became synonymous with the Society of Urdu Literature, an organization he founded in 2008 to promote the Urdu language and literature. The society is known by its acronym SOUL, and has, over the years earned a reputation for being a platform that features top-quality Pakistani, Indian, and American writers and also affords opportunities to children to express their views in the Urdu language.

As a result, SOUL has emerged as an important platform for Pakistanis and Indians who consider Urdu as an integral part of their identity, culture, and ethos. The significance of such a literary and linguistic platform has increased manifold in this era of digital technologies, where, some languages, despite having a presence on the web, see the English language as dominating the discourse.

In America’s multicultural environment of hyphenated identities, critics believe immigrants enjoy more freedom and opportunity than in some European countries to retain and express their social identities while adjusting themselves to the American culture. Still, it is seen as a challenge for immigrants, particularly parents, to steep their children’s growth in their native language.

Pakistani Americans are no exception to the identity and culture challenges immigrants from around the world face as they seek to settle down in a new environment.

As expressed by Naghmi, it was also his love for his Urdu language that motivated him to launch SOUL.

But perhaps, the greatest contribution that SOUL made, under Naghmi and his respected wife Yasmeen Naghmi, has been to encourage family participation in conversations, where both children and parents could own it. On several occasions, they encouraged children to write, even in the so-called Roman Urdu, to describe their experiences or their poems and stories.

The Pakistani diaspora also wants their children to learn Urdu and at least some distinctive traditions of their native culture. The new generation of Pakistani Americans instinctively learn the language at home and become fluent in spoken Urdu but when it comes to writing, or even reading Urdu works, they find it hard to do so.

Noam Chomsky, the acclaimed American linguist, says every child is born with the biological predisposition to learn any language. This means humans have a genetically implanted structure, known as a Language Acquisition Device, which enables kids to understand the rules of the language being spoken around them.

This has been largely accepted. But the U.S.-born kids find it hard to read and write Urdu primarily because they spend their time and attention on their studies. So, the onus is on the parents to see how far their kids could learn to read and write Urdu.

Chomsky’s point, in some ways, also illustrates the question as to why language is so important to human identity, which the people of now everywhere are trying to protect in the face of a 24/7 digital onslaught and an ever-growing glut of narratives.

Immigrants all over the world are particularly very sensitive to the need for passing on their culture, language, and traditions. Such debates on critical aspects of their identity grew manifold in the post-colonial times and more recently after post-9/11 events.

Among the many traits of cultures, language is described as the single most important factor in endowing people with their unique identity. As brilliantly identified by American-Palestinian culture critic Edward Said in his book Orientalism, language was one of the tools the West, the colonizing Europeans, employed in presenting their culture and way of life as superior to those of the East, the colonized nations.

The constant debates on cultures, identities, and political issues in “us vs them” terms and never-ending attacks on the otherness of others in parts of the media around the world have also heightened people’s sense of their identities. Fortunately, America allows people to grow as distinctive ingredients of a salad bowl, where everyone may retain their identity while being part of the whole.

In recent decades, America has benefited enormously from the skills immigrants bring in such fields as information technologies, medicine, and academic research. The advancement of languages on American soil also bodes well for America, as it draws on linguistic diversity to pursue its foreign policy.

Viewed in this context, Abul Hasan Naghmi did a great service to the Pakistani-Americans and Indian-American lovers of the Urdu language. Several other authors and poets are also serving the cause of Urdu in the United States and Canada. Similarly, Pakistani and Indian-origin immigrants have done some great things to promote the Punjabi language with Pakistani author Dr. Manzur Ejaz being one of the leading voices to have introduced the Punjabi language and literature.

I was lucky to have the opportunity to discuss with Naghmi some aspects of his endeavors and his insight on literature, both during interviews and informal exchange of ideas. I remember how he related to me the experience when Noor Jehan, known as the Queen of Melody, decided to lodge in Radio Pakistan for recording national songs to encourage the people to defend their homeland during the 1965 war. Naghmi said Noor Jehan’s decision inspired poets, directors, and the orchestra to come to the radio to record her performances.

Naghmi also worked with the founder of modern journalism Zafar Ali Khan. He had a close association with the finest Urdu short story writer of the 20th century, Saadat Hasan Manto. Once, Naghmi said he had suggested to Manto a correction in a word, which Manto did without entering into any argument. But, fifty years on, Naghmi chanced to look at that word in the dictionary and realized that it was Manto, who was right, not him. The public acknowledgment of the mistake indicated that Naghmi was open to accepting if and when he was not right on a certain point. We also discussed Iqbal and Ghalib. Once, he told me that a native Urdu speaker, during a discussion, said he did not find Iqbal to be an interesting literary light. Naghmi told him plainly that you need to qualify yourself to appreciate the aesthetics, breadth, and depth of Iqbal’s poetry.

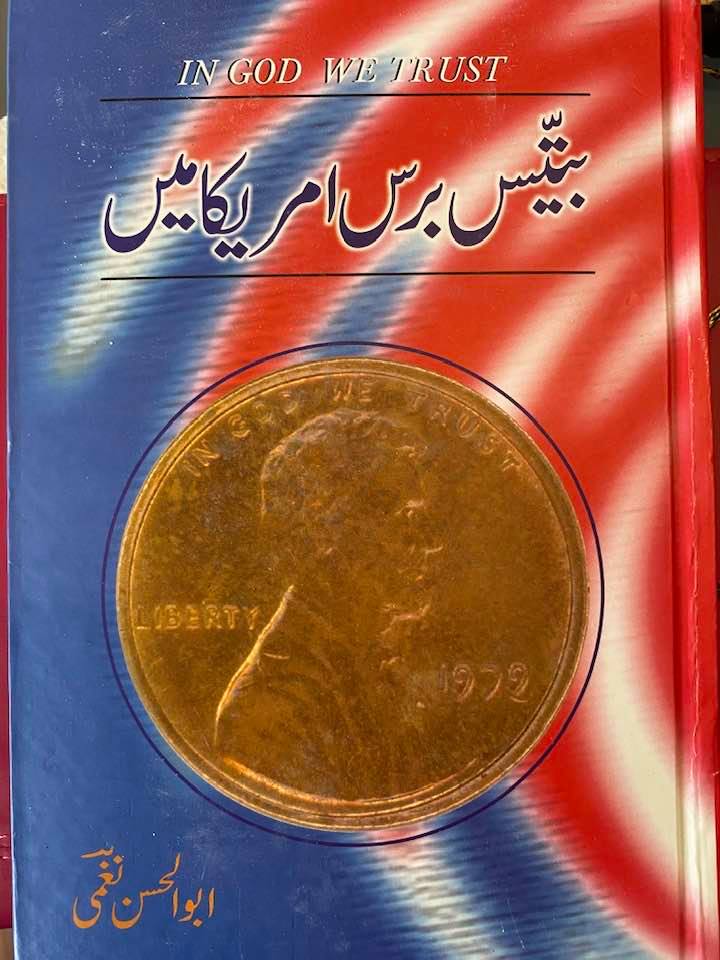

Naghmi, the author and a sensitve member of the diaspora, brought a unique perspective, which he developed over his productive years – from being a native of Lucknow to working at Radio Pakistan in Lahore, the center of Punjabi and Urdu literary flowering, and then as an American, living in a globally influential country.

The death of an enlightened leader is a great loss but the occasion also reminds people that celebrating a successful life also inspires others.

So far, SOUL as an organization has eluded divisions, a rare feat for a Pakistani-American organization. After Abul Hasan Naghmi’s departure, the SOUL leadership has some big shoes to fill and run the organization efficiently in service of the diaspora and the cause of the language.

Thanks for the (tribute) write-up about Naghmi sb and also attributing the “rare feat” he managed in keeping the Soul equally acceptable to all Pakistani Americans (in a way painful too).

But interesting is also the language orientation aspect that can help many to think on lines as how to keep their offspring abreast of their native language (s).

Wonderful article