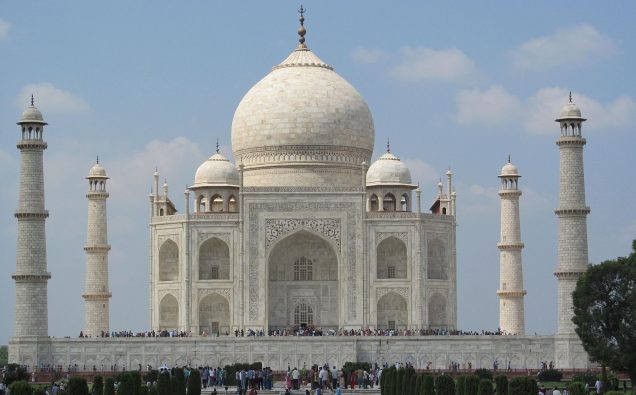

Taj Mahal, a symbol of love, was built by Emperor Shah Jahan, father of Dara Shikoh and Aurangzeb, in the 17th century, Image: Rajesnewdelhi/Wikipedia

THE BRIGHT LIGHT

When in 1652, Dara Shikoh was formally declared the crown prince of the Mughal Empire his future seemed secure. He was given the title “Padshahzada-i-Buzarg Martaba,” son of the Emperor with the status of a Saint. He was also given the highest rank in the Mughal army which came with a command of 40,000 horse and 50,000 troops (Babar, the founder of the dynasty, had conquered India with about 10,000 troops).

Dara Shikoh became the glittering symbol of the golden age of Mughal art, artists and architecture. Not only was he beloved of the emperor but the people of that vast empire had great hopes in him – the Sikh Guru Harrai, the celebrated Muslim mystic Mian Mir and the Hindu pundits who worked with him in translating the Upanishads held him in high esteem. When he fell seriously ill there were prayers for his recovery in mosques, temples and churches.

Millions were spent on his marriage to his cousin Nadira Banu Begum, the direct descendant of Akbar the Great, which was the stuff of legend. This after all was the future emperor of the richest empire in the world and both Dara and Nadira belonged to a dynasty known for extravagant ceremonies with excessive glitter and gold. Nothing like the lavish wedding had been seen before. The marriage is depicted in several brilliant miniatures.

Unlike the male members of the dynasty who often had numerous wives and concubines, Dara was content married to Nadira Banu Begum. He had a happy relationship with her and addressed her as “dearest intimate friend”.

![A miniature portrait of Dara Shikoh Image Credit: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston [Public domain]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e2/Unknown_Indian_-_Miniature_Portrait_of_Dara_Shikoh_-_Google_Art_Project_%28cropped%29.jpg)

A miniature portrait of Dara Shikoh Image Credit: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston [Public domain]

Dara Shikoh was then just preparing his seminal work, Majma-ul-Bahrain, the Mingling of the Oceans– from which we derive the title and concept for my article. Dara Shikoh, unlike the traditional mystic, was guided not only by the instincts of the heart but, a rare quality, also by rigorous reasoning.

He laid out a thesis and then set out to marshal the evidence and prove the thesis correct. He proposed that the two great Oceans of faith, the Abrahamic and non-Abrahamic, are intrinsically linked.

He called his study The Mingling or the Confluence of the Oceans. He was certain he had found the connection at the heart of the faiths.

Having translated 50 Upanishads with the aid of learned pundits he argued they were in fact nothing less than the “Kitab el maknun” or the “secret verses” of the holy Qur’an. This he called the “Sirr-e-Akbar” or the Great Secret.

The marriage of Dara Shikoh and Nadira Begum Image from Brooklyn Museum/Wikipedia

He had found the bridge between the Abrahamic faiths, here represented by Islam, and the non-Abrahamic religions represented by Hinduism. Together they represented a major percentage of the world’s population. In terms of milestones in religious literature, Dara’s Majma is no less significant as Augustine’s The City of God and Aquinas’s Summa Theologica.

Yet, Dara Shikoh’s world would change abruptly. The Greeks have a word for it – given to us by Aristotle: it is peripeteia. This concept is at the heart of what we know as Greek tragedy.

THE DANGEROUS GAME

Dara was playing a dangerous game. He should have heeded Nizamudin Aulya, the Saint of Delhi, who famously had two large arched doors one in front of his seat where he received visitors and one behind him. When people asked him about the gate at the back he replied: if I see the king or governor entering from the front gate I will disappear from the back. In short, a true Sufi stays far from power which is seen as corrupt and corrupting.

In less than a decade from the time he was welcomed as the crown prince, he was betrayed, deserted and executed. He was defeated at Samurgarh near Agra. Dara was then chased by the Mughal army while Aurangzeb turned to deal with another brother. Dara kept one step ahead of the imperial army losing every skirmish and seeing his supporters dwindling.

There was no hope and no help from any quarter. He was now so disoriented and pessimistic that his beloved wife Nadira Begum could not bear to see her beloved prince falling apart. She took her life, further plunging Dara into deeper gloom. The great imperial philosopher and mystic who promoted love and compassion was now totally alone. He had no idea how to deal with his predicament. At this point he was betrayed by his host Jiwan Khan and handed over to Aurangzeb who was ready to have him tried and declared an apostate. The death sentence followed. But not before one final indignity.

Dara was dressed in rags and placed on an old sickly elephant covered in dirt and paraded in Delhi. The crowds, who had been encouraged to turn out and see their beloved Dara, were shocked and turned their backs in protest. When Jiwan Khan rode by he was greeted with catcalls and booing. But no one pulled a sword to protest the condition of Dara. His once loyal supporters were ready to follow him to temples and mosques but there was a clear boundary beyond which they would not proceed.

Dara Shikoh with his army, Image: By Unknown / Public Domain/Wikipedia

Not for the first – or last- time was a Mughal prince realizing it is a lonely, cruel and cold world when he is stripped of power and privilege; that failure has no fathers and even close friends disappear at its sight. Just as Dara appeared bold and successful in his interfaith endeavors, on the battlefield he was unsure, lacked fire and exhibited poor leadership. As a rule a Sufi mystic makes for a poor general and it is best for all concerned if he not be given charge of an army in combat.

Dara waving a sword sitting atop a battle elephant was as incongruous in the imagination as Aurangzeb, after imprisoning his father and doing away with brothers, nephews and sons, in the guise of an austere fasting Saint humbly bowed on a prayer mat before God. These images challenge us precisely because the discussion about these two brothers is cast in the form of straightforward binaries: the elder brother, the crown prince, wanting peace and harmony with all versus the evil and violent younger brother plotting to usurp the throne.

The reality is much more complex and hints that the brothers are locked in a bitter sibling rivalry as much as fighting for the throne. Aurangzeb after he executed Dara taking Dara’s favorite Hindu protégé into his own harem and killing the mystic Sarmad, Dara’s favorite, when he was no threat may be explained more in terms of psychological compulsions than political gains alone.

THE ABRUPT TURN IN INDIAN HISTORY

As for the Majma, this brilliant and seminal achievement in spiritual harmony that could have changed the shape and destiny of South Asia was reduced to rubble when Aurangzeb had Dara beheaded. It was a death foretold as the younger sibling was already busy building a case against his elder brother arguing that Dara was an apostate deserving death. Did he not equate the Hindu scriptures to the Qur’an and thus commit sacrilege? In this case sibling rivalry changed the course of history. The notion of Mingling took a hit and for the next few centuries Muslims were wary of moving towards spiritual adventures. As for the Hindus, they soon saw Dara Shikoh as an aberration.

In time they said Islam was more represented by the orthodox and bigoted younger brother. His beloved wife Nadira Begum committed suicide, his sons and nephews were killed and his revered father was jailed. The man who was inflicting this cruelty on Dara Shikoh was his own younger brother Aurangzeb. Aurangzeb used Dara’s book on the Mingling as his main argument to mobilize court opinion against Dara.

The book now became a millstone around the neck of Dara and Ulema argued that as an apostate he deserved death. Aurangzeb’s hatred knew no bounds. Once Dara lost the battle at Samugarh near Agra, it was all over. After a series of skirmishes, as Auranzeb’s army chased Dara’s dwindling numbers, he arrived at the estate of Jiwan Khan whose life Dara had saved several times and found treachery waiting for him. He had Dara and his son handed over to Aurangzeb. Aurangzeb had Dara beheaded and in a fit of rage slashed the head with his own sword thrice. He then had the head placed in a box and the box on a plate which was sent to his imprisoned father with a note saying “your son has not forgotten you.” At which the former emperor expressed his delight and “thanked God that my son has not forgotten me.” When he opened the gift he fainted and in doing so injured himself.

Aurangzeb did not spare his brothers nor his own son. But his close family was not his only target: he had Sarmad and Guru Tegh Bahadur, the ninth Guru and the head of the Sikh community, executed; perhaps because they were close to Dara Shikoh. The Guru’s close advisor Bhai Dayala was boiled alive. Pathan leaders in the north and Shia leaders in the south were all his targets. There was a demonic fury and psychotic hatred in Aurangzeb’s extraordinary acts of bloody cruelty which would have sent Macbeth scurrying for pen and paper so he could write down tips from the master.

Humayun’s mausoleum, Delhi Image:https://www.flickr.com/photos/michaelclarke/ Wikipedia

As emperor, Aurangzeb proved to be an austere ruler attempting to live by certain values. He accused Jiwan Khan, who was expecting a reward: How dare he lay his hand on a prince of the Mughal family? He conferred the highest title of PadshahBegum on Jahanara in spite of her full support of his brother Dara and father. He now developed aspects of religiosity which to this day impresses Muslims and convinces them that Aurangzeb was a saint. For forty days every year he slept on the floor, fasted and withdrew from public life. He donated the small sums of money he earned by making caps and copying the Qur’an to the building of mosques and temples. He also began to ask searching questions about his own behavior in the past and challenged the Ulema around him who supported him blindly as “Wali ullah”— or friend of God.

Under Aurangzeb, the Mughal empire was at its largest ever and effectively united India, from Afghanistan to Burma and Baluchistan to the deep south of the peninsula. It comprised some four million square kilometers and had a population estimated at 180 million people, India was then the world’s largest economy and manufacturing power having overtaken China. It is estimated by historians of India like Dr Shashi Tharoor and William Dalrymple that India then produced about 25% of the world’s GDP, more than all of Western Europe put together. Its largest and wealthiest province, Bengal, was the best example of proto-industrialization. When the British left after 200 years of colonization India’s GDP was reduced to about 2%, and Bengal was reduced to an impoverished and famine prone area.

THE JUDGMENTS CONTINUE

Today, with the RSS drive in India to bludgeon, lynch and burn non-Hindus in an attempt to convert them to Hinduism, the marauding mobs chant, “Aurangzeb Ki awlad , Yah qabiristan yah Pakistan”- “children of Aurangzeb, either the grave or Pakistan for you.” Many believe, the RSS, which follows the exclusivist Hindutva ideology and influences BJP policies, is clearly using Dara Shikoh for its ends.

Dara in the meantime, in one of those strange twists of fate that leaves us baffled at her fickleness, has been discovered by the RSS as “the good Muslim” in contrast to the “ bigoted Muslim” Aurangzeb.

In Pakistan, Aurangzeb remains an iconic champion of Islam, while Dara is relegated to the margins of history and viewed with suspicion as a confused apostate. Few have heard of him, fewer remember him. The colleges and highways of Pakistan are named after Aurangzeb, rarely if ever to honor Dara Shikoh.

But now there has been a renewed interest among Pakistani intellectuals in Dara Shikah and his works.

At school in Northern Pakistan I had not been taught anything about Dara Shikoh nor had any idea who he was. In our history lessons we viewed Aurangzeb as a defender of Muslims along with the other champions of the faith like Sultan Saladin. It would be years before I realized the true nature of Dara Shikoh and Aurangzeb and the complexity of their relationship. I also realized that the issues their lives raised are very much with us today.

Going into the future we are thus faced with three broad choices. The first is to leave things as they are which is a constant Clash—or possibility of a Clash—of Civilizations, an idea made popular by Samuel Huntington.

Much of the media and too many leaders today are influenced by it and it has shaped the malevolent Islamophobia that has spread like a virus. The second alternative is to continue the Dialogue of Civilizations with its limited impact. The third is to find other methods to live in peace. The first is not viable without eventually reducing civilization to rubble and the second will not really go anywhere judging by its performance so far in spite of the heroic efforts of individuals.

THERE COULD BE ANOTHER WAY

We must therefore develop a third way. That leaves us with no recourse but to explore our own path to Mingling. But we need to clarify what precisely we mean by the concept and then to suggest a way forward.

To reject Dara Shikoh because he failed to gain the throne and lost his life is similar to rejecting the concept of philosophy because Socrates lost his, or rejecting the notion of compassion and embracing humanity because those who advocated it, from Jesus to Mahatma Gandhi to Martin Luther King Jr, lost theirs.

Although little may remain of Dara Shikoh’s political legacy, the message and spirit of his book The Mingling of the Oceans, is of significance for us in the 21st century, especially in the context of the violence and confrontation taking place between and inside the faiths across the world. It leads me to believe that perhaps Dara’s time has come.

Editor’s Note: This piece is being repubished as the author nears completion of the book. It originally appeared in the Views and News in 2019, when the author embarked on the book project.

Thank you Professor for enlightening our world

As ever, with gratitude and respect

Hello my friend! I wish to say that this article is awesome, nice written and come with almost

all important infos. I would like to look more posts like this .