By Sahibzada Riaz Noor

The tradition of scholar-administrators in British India did dwindle after partition, but totally extinct it did not become. Despite the censorious cavilling about civil servants from various quarters for being high browed mandarins cut off from the commonality, here we have in a worthy coalescence, a compendium of two books by outstanding civil servants, Sir Evelyn Howell, ICS and Dr Akbar Ahmed, contributing to the understanding of the proverbs spoken among common Pakhtoons and of British dealings with the indomitable Mahsud tribe of Waziristan in particular, and the Pakhtoon tribesmen in general, during the early years of the advent of the colonial power on the tribal scene.

Thus we are provided with an invaluable insight into the cultural norms, values and way of life of this fiercely independent people and the lessons the British learnt in their interactions with this most intractable race that has defied occupation or subjugation by any conquering power for over three millenniums. Mataloona (proverbs) and Mizh (‘We’ in Karlanri pakhto dialect spoken, among others, by the Mahsud tribe) are imbued with both the eye of scholars as well as a deep respect for and the urge to understand the life and honour code of the Pakhtoon that moulds and guides the life of these people from time immemorial, of both lay and the privileged.

Mizh was written by Howell (1877-1971) as an official monograph recording British dealings with the Mahsud, the most intransigent tribe of Waziristan, from 1860 up to 1925. Howell served both as Political Officer, South Waziristan and later as Resident, Waziristan. Coincidently, Dr Akbar Ahmed, about a century later, served as Political Agent, South Waziristan and in a labour of love, in 1974, published Mataloona, an English translation of 164 pakhto proverbs with a preface penned by that other great frontierphile, Sir Olaf Caroe, ICS, author of the quintessential work on Pakhtoons, The Pathans.

Oxford University Press and Dr Ahmed, now occupying Ibne Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies at the American University, Washington, DC, deserve our appreciations for restoring by republishing two precious contributions to understanding the ‘nang’ Pakhtoon, chiefly those living in the tribal districts who, after passing through a period of war and turmoil over the last four decades, now loom large once again in contemporary geo-strategic shifts and changes in the region. Of particular relevance are these two short works as the tribal areas of Pakistan are being assimilated into modern democratic, lego-state structures with attendant challenges and opportunities with the need to balance integration with regional autonomy.

In a metaphoric sense, whereas Mataloona provides the warp, Mizh is like the woof in trying to appreciate the British playing out the ‘ Great Game’ by enacting the Forward Policy in India’s frontiers during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The daunting challenges encountered in trying to extend the writ of the state over the infractions tribes, in the backdrop of the values that are reflected in the proverbs and culture of these hardy people driven by ‘nang’(honour),’ toura’(courage)and ferocious guardianship of ‘ khawra’( motherland), are thrown up in stark colours with priceless lessons for present policymakers and local administrators.

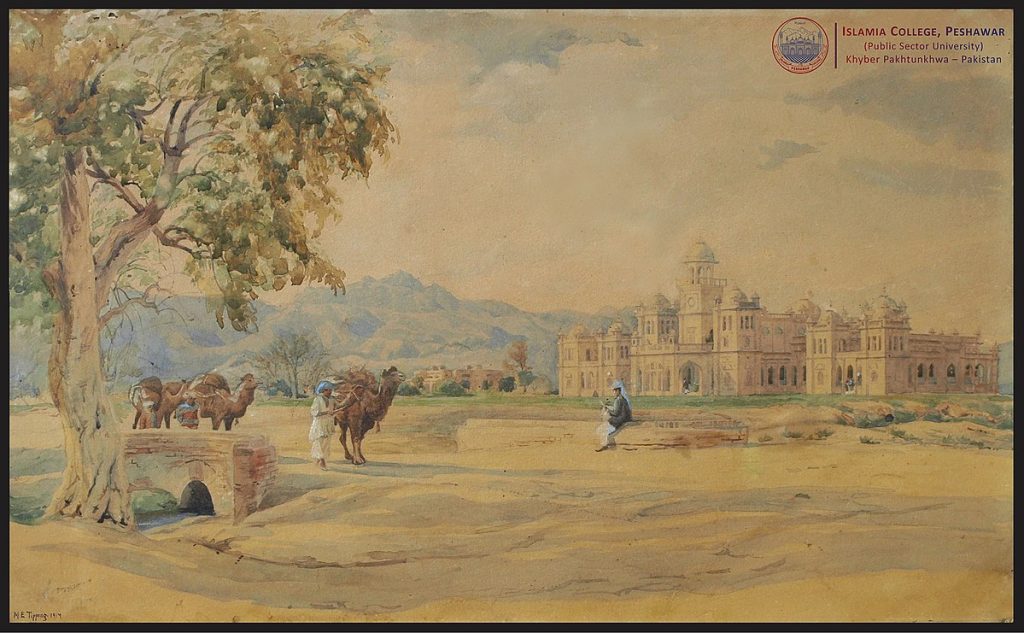

All the three former civil servants, Howell, Caroe and Ahmed share that exhilaration of the spirit that many a frontier officer has felt when crossing the Indus at Attock bridge

knowing,in Caroe’s words, that however hard the ‘ task beset with danger, here was a people who looked him in the face and made him feel he had come home’:

چرته. چه ږړه ځی هلټه ښپسئ ځی

Where the heart goes the feet follow

Mataloona reveals that the pith and marrow of Pakhtoon proverbs consist upon the primal

values of the Pakhtoonwali code of life comprising of nang (honour),names (female honour), melasma (hospitality),turah (courage),badal ( revenge), nanawati (protection to one seeking refuge or generosity towards the defeated), qawl ( keeping word),bakhal ( forgiveness), wapa ( loyalty),khaigara (kindness),patt aow wyar (respect and pride) ,da khawrai pour (protection of one’s country). A Pakhtoon’s pride in one’s soil is indicated by:

ی هرچا ته خپل وطن کشمېر د

To every man his own country is Kashmir

Tolerance and readiness to compound disputes through negotiations are for ever prescribed:

چه اوښان ساتۍ ورونه ستر ساته

Power asks for large-heartedness

If you keep camels keep your doors tall

غر په غر نه ورځی بنده په بنده ورځۍ

A mountain to another does not go

But a man to another does

It is a measure of the professional honesty of Howell when he decries the ‘ utter futility’ of all the various policies adopted by the British to subject the Mahsud’s to some measure of peace and order while admitting to the failure of any military solution to the Waziristan problem. That this was so due to being faced by an implacable race of people to whom being defeated was worse than a thousand deaths:

سل ځلی مۍ مړ کړۍ په ښاورۍ او ننګ مۍ ېو ذل مړ مه کۍ

A hundred times death is acceptable

But not once for country and honour

Although the British formally established contact with the Waziristan tribes in 1860, such was the stubborn intransigence they encountered, that setting up of a camp at Wana was only possible 35 years later in 1895 and at Razmak in 1922. But the British found hardly a day of peaceful respite from ceaseless by the raids and attacks by the Mahsuds on camps, posts and convoys. Between 1860 and 1925 countless infractions and raids were made on D I Khan, Bannu, Tank, Wana and posts and picquettes inside Mahsud territory in which about 54 British officers were killed including four political officers.

Such was the obdurate local opposition to securing a durable settlement to the Waziristan problem that even Viceroy Curzon was forced to remark that no patchwork of blockades, allowances etc would find a solution to the tribal predicament ‘ until the military steamroller has passed over the country from end to end …’ But as a true observer of history and a perceptive spectator of human affairs amidst this challenging and relentless environment, he readily acknowledged the limited chances of any military solution to the tribal issue and hastened to add: ‘ But I do not want to be the person to start that machine.’

Underlying accounts of administrative affairs in the borderlands, a central undercurrent in Mizh is keen respect for and desire to understand the Mahsud tribal society, its language and way of life.To the British political officer’s claim of being the custodian of civilisation, Howell states that a Mahsud malik’s retort would be: ‘ A civilisation has no other end than to produce a fine type of man. Judged by this standard the social system in which the Mahsud has been evolved must be allowed to surpass all others.

Therefore, let us keep our independence and none of your “ qanun” and your other institutions which have wrought such havoc in British India, but stick to our own “ riwaj” and be men like our fathers before us.’ And Howell readily observes:’ After prolonged and intimate dealings with the Mahsud I am not at all sure that , with certain reservations, I do not subscribe to their view.’

A telling anecdote on how not to deal with Pakhtoon tribesmen is found in Caroe writing as Governor, NWFP in October 1946 to Viceroy Wavell about the disastrous visit to tribal areas by Jawaharlal Nehru. Apparently, tribal maliks had taken umbrage at being described as ‘ pensioners’ by Nehru and had to face stoning and attack on his person in Jamrud and at Razmak from which Nehru came away shaken and slightly injured. About Nehru, Caroe wrote:’ ….these people are far too intense to deal with tribesmen.

They do not understand that a steady bearing, turning off to a smile or joke when tempers get frayed is the proper way to deal ( with these tribesmen)’. As a tribal malik would exclaim:

Even though a straw I am sufficient for you که خس ېم د تا بس ېم

Howell must have often come across among the formidable Mahsuds the unwavering tendency not to pardon a foe even if it took a hundred years to take revenge ( basdal):

پختون سل کاله پس بدل واغست وېل زر مې واغست

A Pakhtoon taking his revenge after a hundred years said I took it early.

Mullah Powindah was perhaps the greatest threat to British authority and safety of its men in Waziristan right upto his death in 1914. Yet we find unmistakable esteem, respect and chivalry in the words in which Howell describes a violent and bitter foe upon his demise quite unlike utterances made for opponents of stature when they were killed in many later times: “ …he cannot be denied some tribute of admiration as a determined and astute…. patriot and champion of his tribe’s independence…a man who without any inherited advantage (or) education could make so large an instalment of frontier history…can have been no little man and given …a more fortunate setting in time and place, he might well have ranked with many who are accounted, great men.”

Several topical and prescriptive conclusions can be safely derived from Mizh and Mataloona that are invaluable for both the general reader as well as policymakers and administrators, both civil as well as military. A comprehension of the history and respect and reverence for the culture, language and norms of the Pakhtoon tribes coupled with the realisation of the limits to finding solutions through forceful means can yield far more rewarding results of durable nature and willing acceptance. Mainstreaming of ex-Fata regions should aim at the extension of modern legal- constitutional and administrative structures along with the benefits of civilisation. Yet assimilation must not be at the cost of exclusive marginalisation, and a sense of healthy participatory belonging is required to be created with preservation of local traditions and identities along with living empowerment over lives and resources. The higher level of administrative training of officers at the Institute of Public Policy and NDU would certainly benefit a great deal if this book is made part of the reading list of these institutions.

Author is a noted poet and writer, and served as Chief Secretary of Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.