Where can we find “unity in diversity”? This question is on the minds of many in today’s tumultuous network of political, cultural, and religious rivalries, which made the lecture event that took place last week all the more essential. On the evening of July 8th in Washington, D.C., and the morning of the 9th overseas, the Institute for International and Area Studies (IIAS) at arguably China’s premier University, Tsinghua University in Beijing, China, hosted a lecture given by Ambassador Akbar Ahmed.

The event was organized by the distinguished Professor Tingyi Wang, a Faculty member of the University. Ahmed was introduced by Dr. Louis Goodman, the Dean Emeritus of American University’s School of International Service (SIS), who called him “one of the world’s preeminent scholars on Islam”. Ahmed is the Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies at SIS, the former Pakistani High Commissioner to the U.K. and Ireland, and a decorated author, anthropologist, filmmaker, and prominent advocate for religious understanding. The presentation was inspired by his most recent book, The Flying Man, Aristotle, and the Philosophers of the Golden Age of Islam: Their Relevance Today.

The Golden Age of Islam was incredibly influential for the other eras of cultural and scholarly progress, and yet, as Ahmed notes, it often remains unexplored in world history lessons despite its contemporary value. The word “La Convivencia” or ‘the coexistence’, was created by the Spanish to describe this period of intellectual cooperation among cultures and religions.

This movement spanned 3 continents, Africa, Europe, and Asia, between the ninth and thirteenth centuries, and the historical remnants of this time still exist in areas such as Andalusia, Spain, or the writings of the American Founding Fathers. The roots of modern philosophy, science, and religious harmony can be traced to this place and time.

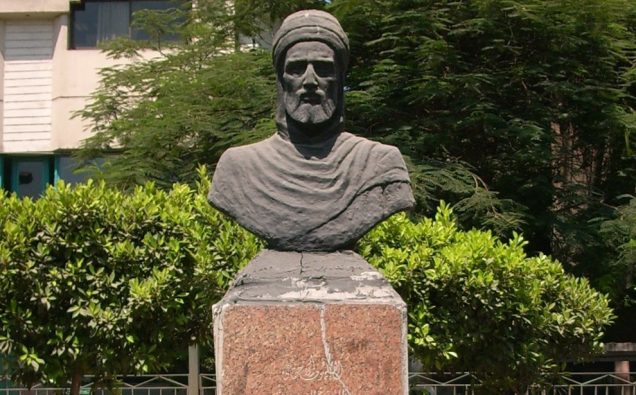

The Ambassador covered many of the most important figures in the Golden Age, including Christian, Muslim, and Jewish scholars, but none stood out as much as Ibn Rushd. One of the original ‘Renaissance Men’, Rushd (also known as Averroes) wrote over 100 books, and found philosophical ways to harmonize faith and science, scholarship, and mysticism. His work was deeply admired by St. Thomas Aquinas, one of the most important Christian scholars of the time, who referred to Rushd simply as “the commentator”. “God will never give us reason and then give us divine laws that contradict such reason,” said Aquinas echoing Rushd.

Among the students from Tsinghua University in attendance, Dean Goodman, Senator Mushahid Hussain, and Dr. Amitav Acharya, all visiting scholars and respected figures at the Tsinghua University, were also present. Acharya was the first to give feedback on Ahmed’s enlightening remarks, saying “The past is never quite the past, and contains the knowledge to help us through the future,” he said.

The scholars of the Golden Age were also invaluable transmitters of ideas, said Acharya, noting that Aristotle’s Metaphysics survived only in Arabic. He gave glowing praise for the work that Ahmed has done to ensure that the true history of Islam is preserved and shared in the West. He also cautioned against placing greater weight in the words of popular media as opposed to scholars. Citing Graham Allison’s theory of Thucydides’ Trap, world powers often demonstrate a proclivity for war when they feel threatened. Thus, it is often the work of scholars to foster intercultural communication during periods of international unrest.

Pakistani Senator Mushahid Hussain Sayed, Chairman of the Pakistan-China Institute, echoed these thoughts and added his own reflections. He reminded the students that many of the values held most important in Chinese culture are “congruent with the values of Islam,” such as a reverence for scholarship and the importance of respect. Senator Hussain also emphasized that this is such an extraordinary event because the participants are in three important world cities, with Ahmed’s team in Washington, D.C., the Senator in Islamabad, and the hosting University in Beijing. He said that the Ambassador is playing the role of a vital “bridge” between these three points. One of Ambassador Ahmed’s former students, Frankie Martin, added that the Golden Age of Islam is a beautiful example of how civilizations are enriched by one another.

I was impacted by this lecture in two ways. First, I was mesmerized by the swarth of accomplishments that can be attributed to the Golden Age of Islam. There are so many pieces of our collective, global history that have been overlooked, and this lecture exposed a gap that so many have in the stories that we tell about the evolution of human societies. The invention of the camera obscura by Ibn al-Haytham, for instance, made the very Zoom meeting we all attended a possibility. Ahmed also insightfully remarked that Muslims everywhere will feel empowered as global citizens if their cultural accomplishments are highlighted, giving them a sense of pride in their identity. Second, I heard in the Ambassador’s words a sort of proof: proof that collaboration rather than competition is possible, proof that forums to share scholarship among civilizations have existed for centuries, proof that we have been here before and emerged more equipped to handle hardship. Climate change, religious and cultural violence, and the COVID-19 pandemic have all rendered us more concerned about the future. In this context, Ambassador Ahmed provided three goals that we must set to take on these challenges. He said that we must look at other cultures to better understand our own, we must abide by the Confucian rule of “treating others as you would like to be treated”, and we must acknowledge learning as central to the human experience.

I feel so lucky to have had the opportunity to both attend and write about this lecture because of the great example it has set on the international stage. It is not often that the accomplishments of Muslims are internationally revered outside of the Middle East, and so the Golden Age of Islam serves as a reminder of the importance that Islam places on Ilm, or knowledge. I am incredibly proud that Ahmed, a professor of mine, has continued to promote tolerance and scholarship, and I am in awe of the genuine, mutual respect I observed. Like the works of the Golden Age scholars, I hope that The Flying Man might also be translated, a proposal that came from Professor Acharya, to ensure that global audiences can enjoy his work. One of the most impactful verses in the Quran says, “the ink of the scholar is more sacred than the blood of the martyr.” Phrases such as this one are a reminder that all humans, regardless of culture and ethnicity, have shared curiosities about the world. We see very few instances of true collaboration between the U.S., China, and Pakistan in the modern era. However, Ahmed called on the poetry of Wang Changling to describe this forum, saying: “the bright moon belongs not to a single town, but to all of us.” We are all under the collective darkness of the pandemic, of violence, and of misunderstanding. Thus, we must all be part of generating and sharing the light of Ilm, for that is the only true way to brighten the path to peace and harmony in the future.